Desert Magazine, August 1954, pages 25-28

By NELL MURBARGER, Photos by the Author

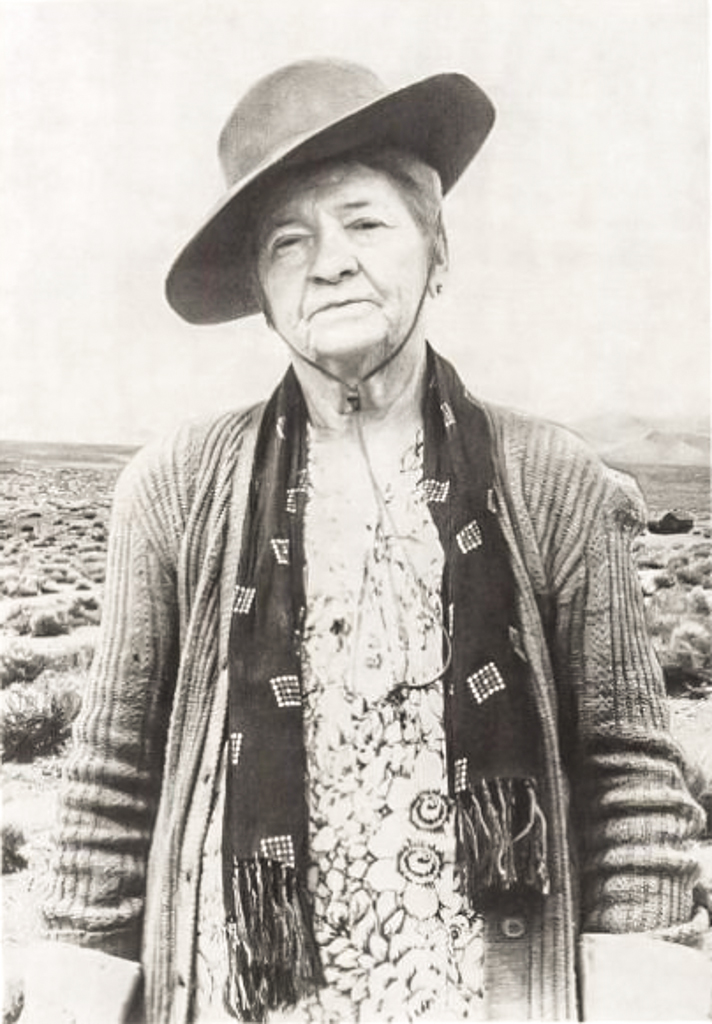

Josie Pearl - her dress was of calico, but in her wardrobe a $7000 mink coat. She lives alone on the Nevada desert many miles from her nearest neighbor. |

Deep in the Black Rock Desert of northwestern Nevada, Josie Pearl lives alone, 96 miles from the nearest town, self-sufficient, and facing the challenge of each new morning with enthusiasm. A desert lady with a desert heart, she has helped sick miners and given needed love to wayward boys. She was at hand when Bob Ford was killed and was a close friend of Ernie Pyle who wrote her, 13 hours before he was killed, "the happiest I will ever be again is the day I stick my feet under your table and eat a pot of those Boston baked beans." |

SPIRALING OUT OF the north, a sinuous dust devil grew as it moved across the desert, gathering more thistles and broken sage, more dust. The dancing column vanished in the heat haze to the south, and the yellow flat slipped back under its briefly-broken hush.

Once again, there was only vastness, rimmed by ragged hills, and marked by the thin tracery of the road.

I was no stranger to this upper lefthand corner of Nevada. I knew the nearest town to the northwest was the one - store - and - postofflce village of Denio, Oregon, 72 miles away; and that to the west, there was no town closer than Cedarville, California, 170 miles.

Between those outposts and Winnemucca to the south, spread 10,000 square miles of sage and solitude, silence and sand - a territory more than one-fourth as large as the entire state of Indiana, but without either postoffice or point of supply.

Somewhere, deep in the heart of that immensity, I hoped to locate a lone woman - a woman who had been described to me as one of the most remarkable characters in the West.

Until two days previously, my acquaintance with Josie Pearl had been limited to three pages in Ernie Pyle's book, Home Country,* a collection of his best newspaper columns originally written and published in the 1930's.

"Josie Pearl was a woman of the West," Pyle had written. "Her dress was calico, with an apron over it; on her head was a farmer's straw hat, on her feet a mismated pair of men's shoes, and on her left hand and wrist $6000 worth of diamonds! That was Josie - contradiction all over, and a sort of Tugboat Annie of the desert. Her whole life had been spent . . . hunting for gold in the ground. She was a prospector. She had been at it since she was nine, playing a man's part in a man's game . . ."

I had read the book, and enjoyed it, and eventually had forgotten it.

Several years passed; and then I happened to be spending a night with John and Marge Birnie, at the Old Mill Ranch, near Paradise Valley, Nevada. As we had sat talking that evening, Marge had remarked that I should write a story about Josie Pearl.

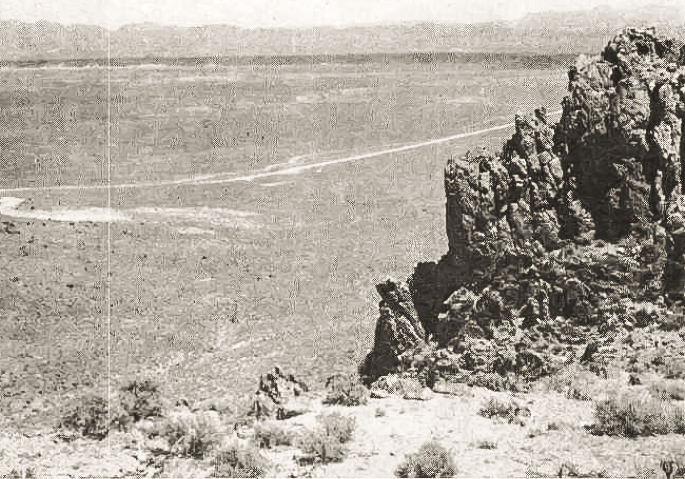

Enroute to Josie Pearl's home, 96 miles from Winnemucca, Nevada, Author Nell Murbarger took this photograph of the expansive desert.

Enroute to Josie Pearl's home, 96 miles from Winnemucca, Nevada, Author Nell Murbarger took this photograph of the expansive desert.

"Not that lady miner Ernie Pyle wrote about in Home County?" I exclaimed incredulously. "Don't tell me she's still alive!" "And going strong!" laughed Marge. "But she's far more than a 'lady miner'! She's a great personality. She's straight out of the pages of the Old West - and she's the last of her kind!" If I had been told that Kit Carson was waitin" for me at the gate, I couldn't have been more astounded. Nearly 15 years had elapsed since Pyle had written his story of this woman; and, even then, he had carried the impression that she was very old. And now, to learn that she was still "going strong" was almost unbelievable.

Although the Birnies knew her well, they could not tell me how to reach her home - a situation I was to find quite prevalent during the next two days, which I spent making inquiries around Winnemucca. Everyone I approached seemed to know her - and favorably - but none could give me explicit directions for finding her.

"I've never been to her place," they would say, uncertainly, "but she lives up near the north end of Black Rock desert . . ." Or, perhaps, they would describe her residence as "somewhere in the vicinity of Summit Lake," or "over beyond the Quinn River Country."

However described, it was vague. But now that my interest was aroused, I was determined at least to make an attempt to locate her.

Because it had seemed the logical approach to any of the geographical points mentioned, I drove north on U.S. 95 to the junction of State Route 8-A, 33 miles beyond Winnemucca. Halting at the turn-off - like a diver hesitating before the plunge - I sat there for several minutes, ranging my eyes over that wide and lonely land spreading ahead; and then, I eased my foot from the brake, and the car and I were rolling down that long, empty road, leading to the west.

In this section of Nevada, human inhabitants are few so the first opportunity I had to check my navigation was at Quinn River Ranch. 38 miles west of the turn-off. Only the ranch cook was in evidence. Like everyone with whom I talked at Winnemucca, the cook knew Josie Pearl, but not where she lived.

"When she goes to town," he said, "she comes up from the south. I'd say take the Leonard Creek road to the next ranch - the Montoya place - and ask there. It's not far," he added. "Maybe 25 miles . . ."

This Leonard Creek Road was a primitive sort, not in the least hazardous, so long as speed was held down, but generally narrow, frequently given to sharp turns, and always dusty. As I dodged sand pockets and shuttled through hedge-like aisles of sagebrush, I thought of Ernie Pyle traveling that same trail all those years before.

"There really wasn't any road to Josie Pearl's cabin," he had written. "Merely a trail across space. Your creeping car was the center of an appalling cloud of dust, and the sage scratched long streaks on the fender."

Leaving Quinn River Ranch, the road skirted the southeasterly base ot Pine Forest range, soon heading west across the northern fringe of Black Rock desert.

Stretching to the southwest for more than a hundred miles, this bleak playa - this barren bed of prehistoric Lake Lahontan - is a place of expansive silence. At its widest point, the playa is nearly 15 miles across. Here, at its tip, it was soon left behind, and the little road went climbing into the rough range beyond.

Another few miles revealed the Montoya ranch - officially, the Pine Range Livestock Company. Here, for the first time, I learned that I was really on the right road, and that Josie's place was only five or six miles back in the hills. Since leaving Winnemucca, 95 miles before, I had been traveling in uncertainty.

At last, I spotted the house in a small clump of poplars, about a hundred yards off the trail.

"Josie Pearl," Pyle had written, "lived all alone in a little tar-paper cabin surrounded by nothing but desert. From a mile away you could hardly see the cabin amidst the kneehigh sagebrush. But when you got there it seemed almost like a community - it was such a contrast in a space filled only with white sun and empty distance . . ."

Bringing my dust-layered car to a halt in the yard, I looked about me. Everywhere there were tables and boxes and benches, each one covered with ore samples, rocks, petrified wood, geodes, rusty relics, purple glass, miners' picks, prospectors' pans, parts for cars, and miscellaneous trivia. At one of the tables, a woman was working, her face screened from view beneath the bill of an old-fashioned sunbonnet.

"Pardon me," I said. "I'm looking for Josie Pearl's place."

"Well," answered the woman, somewhat gruffly, "You've found it! I'm Josie. What's on your mind?"

For the first time since my arrival, she glanced up. I found myself looking into one of the most unforgettable faces I have ever seen. Years were in that face - a great many years - but there was in it some indefinable quality that far overshadowed the casual importance of age. The eyes that bor2d into mine were neither friendly nor unfriendly. Rather, they were shrewd and appraising; as steady as the eyes of a gunfighter; as non-commital as those of a poker player.

She was not a large woman, bhut healthy-looking and robust, with determination and self-sufficiency written all over her. I felt instinctively that should she ever decide to move one of the surrounding mountains to the other side of the canyon, she would go about it calmly and deliberately, some evening after supper, perhaps. And she would move it - every stick and stone of it - and would ask no help.

That was my first impression of Josie. It still stands. She wasn't sure that she wanted her life story written for Desert Magazine.

"Not that I don't like Desert," she hastened to assure me. I do. Good magazine. Good down-to-earth stuff in it. It's just that I don't go much on publicity . . ."

But persistence and persuasion eventually won the day.

"All right," she agreed at last. "Since you put it that way, I'll give you the story - but don't be surprised if you find some of it a little hard to believe. I'm close to a hundred years old, girlie," she went on, her sharp eyes boring into mine, "and I've had about as strange a life as any person living!"

As we started across the yard toward the cabin, Josie glanced at my car. "You traveling alone?"

I said I was. "Good! Then you'll stay overnight." There was no question mark at the end of that statement.

"Her cabin," again to quote Ernie Pyle's observations, "was the wildest hodge-podge of riches and rubbish I'd ever seen. The walls were thick with pinned-up letters from friends, assay receipts on ore, receipts from Montgomery Ward. Letters and boxes and clothing and pans were just thrown - everywhere. And in the middle of it all sat an expensive wardrobe trunk, with a $7000 sealskin coat inside . . ."

The pin-ups were all there, just as Ernie had described them - the assay reports and newspaper clippings and letters and picture postcards and tax receipts and cash register slips. During the considerable lapse of time between Ernie's visit and mine, I'm sure that the collection on the walls had grown progressively deeper; and while I didn't see the $7000 sealskin coat, I'm willing to concede that it was lurking somewhere in the shadows.

"Have a chair," said Josie. "Anywhere you like. Here - this is the best one." With a vigorous sweep of her arm she sent sailing to the floor an accumulation of newspapers and magazines, and motioned me to the cleared seat. "Now," she said, "what is it you want to know?"

The story of Josie's life was presented with as much chronological order as may be expected in a freshlyshuffled pack of cards. It was presented while we were out in her small garden, cutting "loose leaf" lettuce and lamb's-quarter greens for supper, and gathering rhubarb for a pie. It was presented while Josie was rattling the grate and building a roaring fire in the big cookstove, and concocting the rhubarb pie, and grinding meat for hash, and making hot cornbread; while she was out in the chicken yard feeding her assorted fowls and rabbits and gathering eggs, and getting in wood for the night, and filling the lamps and cleaning their chimneys, and shooing flies away from the door and scolding the dogs.

When Josie was still a small child, her parents had left their Eastern home to settle in New Mexico, where her father became interested in mining. It was an interest that quickly communicated itself to Josie, and at 13 years of age - when most little girls of that hoop-skirted era were still playing with dolls - she had found her first mine, subsequently selling it for $5000. By the time of the mining boom at Creede, Colorado, Josie was a young woman, and nothing could keep her from joining the stampede.

"Was that ever a time!" she shook her head with the memory. "I guess maybe you've heard Cy Warman's poem:

"The cliffs are solid silver, With won'drous wealth untold, And the beds of the running rivers Are lined with the purest gold. While the world is filled with sorrow, A nd hearts must break and bleed - It's day all day in the daytime, And there is no night in Creede!

"That's the way it was - everything roaring, night and day. Gambling, shootings, knifings. I got a job as a waitress. Bob Ford and Soapy Smith always ate at one of my tables. Every Sunday morning each of them would leave a five dollar gold piece under his coffee cup for me. Fine fellows, both of them. I never could understand how Bob could have shot Jesse James like he did . . ."

I asked if she was in Creede when Ford was murdered.

"Indeed, I was!" said Josie. "I was waiting table when I heard the shooting and folks began yelling. I ran outside to see what was happening . . . and there lay Bob, all bloody and still. Yes," she nodded, "I was there . . ."

In 1892, Josie became the wife of Lane Pearl, a young mining engineer and Stanford graduate. For a while she operated a boarding house, patronized largely by men from the Chance, Del Monte, Amethyst and Bachelor mines, of Creede vicinity. Later, she and her husband moved to California; then to Reno, where she worked for a time at Whittaker hospital. And then came the strike at Goldfield.

"We were among the first ones there," she recalled. "I got a job waiting table at the Palm restaurant, owned by a Mr. French, from Alaska. He paid me four dollars a day, plus two meals, and my tips. There was no end of gold in circulation, and all the men tipped as if it were burning holes in their pockets.

"Mr. French had a rule against hiring married women, so I had taken the job under my maiden name. Lane would come in and sit down at one of my tables and eat, but we never let on that we were husband and wife. One day, Mr. French said, 'You know, Josie, I think that young mining engineer who eats in here all the time, is sort of sweet on you.' They never caught on."

Home for Josie Pearl is this building "surrounded by nothing but desert," as Ernie Pile once wrote, ". . . almost like a community . . ."

With Goldfield beginning to languish, Lane Pearl was called to take charge of one of the leading mines at Ward, Nevada, a present day ghost town, a few miles south of Ely. He was still employed there when the influenza epidemic swept the country in 1918. Not even the most remote mining camps were spared, and in November of that year, Lane succumbed to the dread malady. He left his wife of 26 years, by then a woman approaching middle age, and at loose ends.

Even the loss of her idolized husband could not dull her love for the rocky soil of Nevada, and its mining towns. Restlessly she began drifting from camp to camp, operating miners' boarding houses from one end of the state to the other.

"At Betty O'Neil, a camp southeast of Battle Mountain, I made $35,000 in three years, running a boarding house . . . and then turned around and sunk the whole thing into a mine, and lost it. More than once I've been worth $100,000 one day . . . and the next day would be cooking in some mining camp at $30 a month! But I always managed to keep my credit good. Right today," she declared, "I could walk into any bank in this part of the state and borrow $5000 on five minutes' notice!"

The older she got, the more mining became an obsession. Eventually she had gravitated toward northern Humboldt county, had acquired some claims there in the hills, and had been working them since.

"Of course," said Josie, "I still do a bit of prospecting, now and then. Just knock off work at the mine, jump in my old pick-up, and strike out to see what I can find. Last week I was up in Idaho, looking at a uranium prospect. Scads of money in some of this new stuff . . . Scads of money!"

At Winnemucca I had been told that Josie had nursed half the sick miners in northern Nevada, and had spent thousands of dollars grubstaking down - at - the - heels prospectors who were eating their hearts out for one last fling at the canyons. When I referred to this phase of her activities, she brushed it aside impatiently.

"My real hobby," she declared, brightening, "is boys - homeless boys. Lord only knows how many I've taken in and fed and clothed and given educations. Lots of 'em were rough little badgers when I got them. Penitentiary fodder- What they needed most was love and understanding and to know that someone was interested in what they did. I'm proud to say every boy I've helped has turned into a fine man - not one of them has gone wrong. I receive letters from them all over the world. Most of them have good jobs; some are fighting with the armed forces; some are married and have families."

The dream of her life, she confided, is to make enough money to build and endow a home for boys.

"Something like Father Flanagan's Boys' Town," she said. "That's all I'm working for, now."

When I asked how she had happened to meet Ernie Pyle, she explained that she had gone to Albuquerque to visit her sister, who lived near the Pyles and had been nursing Mrs. Pyle through an illness.

"Naturally I met them both, and Ernie and I started to talk about the West, and about Nevada, and mining, and I told him that if his travels ever brought him to Winnemucca, I wanted him to come and see me. He said he would - and he did - several times.

"We corresponded back and forth all the rest of his life. In the last let-ter he wrote me, he said 'The happiest I will ever be again is the day I stick my feet under your table and eat a pot of those Boston baked beans!'

"Thirteen hours later," said Josie quietly, "he was killed . . ."

Dark clouds had been bunching over the bare hills to the northwest, and even before we finished with supper, a stormy gale was sweeping across the yard and the air had turned bitterly cold. With the dishes washed, the assorted livestock fed and sheltered and the lamp lighted, we drew our chairs close to the glowing cook stove and there we talked far into the night.

Josie seemed to draw upon an inexhaustible fountain of experiences. She told of loneliness; of what it meant to be the only woman in mining camps numbering hundreds of men. She told of packing grub on her back through 20-below-zero blizzards, of wading snow and sharpening drill steel, and loading shots; of defending her successive mines against highgraders and claim jumpers and faithless partners.

"More than once," she said, "I've spent a long cold night in a mine tunnel with a .30-30 rifle across my knees . . ."

And there had been lawsuits. Lawsuits without end.

"She said gold brought you nothing but trouble and yet you couldn't stop looking for it," Ernie Pyle had written. "The minute you had gold, somebody started cheating you, or suing you, or cutting your throat. She couldn't even count the lawsuits she had been in. She had lost $15,000 and $60,000 and $8000 and $10,000, and I don't know how much more. 'But what's $8000?' she said. 'Why $8000 doesn't amount to a hill of beans. What's $8000?' Scornfully."

How well, how very well, he had known her.

Late that night, long after Josie and I had retired and the fire in the cook stove had died to gray embers, I lay wakefully in the darkness, listening to the wind as it beat at the windows and doors and whistled down the stove pipe and clutched at a piece of loose canvas and flung gravel against the side of the cabin. Now and then a jagged flash of lightning split the dark sky and distant thunder rolled and rumbled through the ranges.

Some time, on the day to follow, I would return to Winnemucca - to electric lights and sidewalks and dime stores and super markets - and Josie Pearl would be left alone to face the recurring storms of this high, lonely land. She would be left alone to cope with possible illness and accident, with primitive roads, and miring mud, and snowdrifts, and summer's withering heat and drouth and failing springs; and, most particularly, with the problem of daily needs that forever roost on the doorsteps of those who live a hundred miles from the nearest town.

It was impossible to imagine a stranger sort of existence for a woman - particularly a woman of advanced years; yet, I had that day seen enough of Josie to know that as long as she lived and retained her health, she would face the challenge of each new morning with hope and courage and a wonderful enthusiasm for whatever that day might yield.

"She's straight out of the pages of the Old West . . . and the last of her kind," Marge Birnie had said. I was beginning to understand what she had meant.