HOME | My

Friend Sanora | Les Deux Megots

| The First Demonstration

March On Washington | It's

Hard To Know | City Hall Demonstration

| Georgia

|

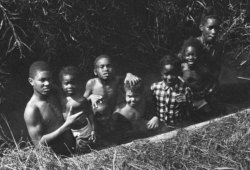

| Georgia In 1969 Bill wanted to visit Georgia after years of saying he would never set foot on Southern soil again, ever in his life. From all he had told me, he had good reason not to return. He was born in 1920 in a rural area called Scarlet Georgia. It isn't far from the Atlantic Ocean and the Florida border. At one time it was a rice growing area. Most of the black people in the area owned their own land stemming from agreements near the end of the Civil War. Despite the black ownership of land, life in Georgia was very segregated. But times they were a'changing as the song goes and Bill went to Maryland in the spring of 1969 to work on a photography project for several days. He had become a good photographer by then. A few days later he called home to say he had finished the job in Baltimore and was going to drive on down to Georgia to his home town, Scarlett and visit any relatives who were still living there. The next day he called again, this time from his Uncle Aaron's house, his voice full of excitement. Georgia had changed. It was beautiful. The obvious signs of segregation were gone. He had stopped in gas stations and diners frequently on the highway south and received good polite service everywhere. Would wonders never cease! "You and Pat are coming down!" He exulted. "The family wants to meet you both." I protested. "It's one thing for you alone, but as a family it's a whole different ball game". An interracial family could be trouble anywhere in the U.S. at that time. To my mind Georgia was like walking into the dragon's mouth. My words fell on deaf ears. He was absolutely convinced the South had really changed. We would come down later that summer together as a family and here was Uncle Aaron to confirm it. Uncle Aaron's rich southern voice on the telephone did not allay my doubts, but I responded politely, if not enthusiastically. "You just c'mon down", he said. "Okay" I answered. I had read and heard so many war stories about the South during these years from veterans of the SNCC* voter registration drives, CORE direct actions, The Southern Christian Leaderhip Council. The conflicts had been bloody and, in too many cases, deadly. The three young idealistic civil rights workers, Chaney, Scherner and Goodman had been found lynched after doing nothing more than trying to register southern Blacks to vote. Four little girls had been killed by a bomb thrown into their church one Sunday morning in Birmingham, Alabama. They hadn't been involved in anything related to civil rights that day. Most recently, Martin Luther King had been assassinated the year before. I also hadn't forgotten the maniacal hatred I saw in the man's face who owned that diner in Maryland years before. "Why don't you nigger-lovers go back where you came from?" he yelled red-faced and sweating. Even though we were going south for a purely private family gathering, I couldn't understand Bill's optimism. I doubted that the sight of an interracial family would go unnoticed by die-hard white segregationists. Things couldn't have changed that much. I figured Bill's enthusiasm would wane by the time he got home and had thought it over. But it didn't. To all who would listen he waxed eloquently on the subject of the new south of the present and his nostalgic memories of growing up there in the past. He decided he wanted to write a history of African Americans in Camden County, Georgia. There already existed a history book of Camden County, but it barely mentioned the existence of Africans, slaves or post Civil War Negroes. It was a white history. There was much to be done, he said. He also wanted to collect books for a library he hoped would be built in Scarlett. While my fears had not exactly abated, my curiosity was growing. I wanted to see this South about which I had heard so much, and curiously, where I had been born. I left my birthplace, Mobile Alabama, at the tender age of 1. My parents were Norwegian immigrants so I did not have a southern heritage, just a southern place printed on my birth certificate. The more I heard, the more I wanted to believe we could keep out of harm's way. I hoped, but wasn't at all sure. As I strapped myself and Pat into the plane seat I regressed into fear. I tried to understand what had led me to agree to this trip. Surely this was folly. Pat was 6 years old. This was only his second plane trip. He was excited by all the buttons and gadgets overhead and on the back of the seat in front of him. Buttons for air-flow, for lights, for calling the attendants and the little table that came down when you turned the hook. I had brought along a bag of new games, toys and books to keep this gregarious ever- active child occupied on the trip.

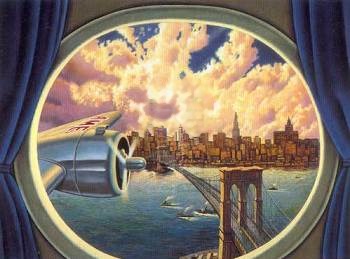

As we took off from J.F.K., I closed my eyes and wondered what was ahead. Bill was not with us. Something had come up with his work and he decided he would drive down a few days later. Maybe that was better. Something about a Black man with a white woman was more enraging to segregationists than a white woman with an interracial child. But one couldn't depend on the consistency of irrational minds. It was time to say something to Pat about where we were going and what might lie ahead. He was happily foraging in the bag of new toys. "Pat, listen to me for a minute. We're going to a place where they used to make black people slaves. Many of the white people down there still want black people to be slaves and are very angry at them because they aren't." How much damage was I doing? Most mothers of minority children feel they must protect by instilling fear and distrust of the majority. I was part of the majority. But I had to communicate something about the danger. I continued, "When we get there, to the airport, I want you to do as I say WHEN I say it. The FIRST time. No fooling around. It's important. It could be really dangerous, I just don't know. OK? The FIRST time." His eyes grew large and he nodded his head. He didn't say anything. I waited for questions, but none came. He waited a second looking at me as if for any further instructions, and then went back to his toys. His lack of questions was unusual. I can only guess that it had to do with the fear in my voice. When we touched down at the Atlanta airport we knew we had a two-hour wait before boarding a small local plane to St. Simon Island, the closest airport to Scarlett. At that time the Atlanta airport was a modern building formed in a sunburst pattern. Pat and I walked hand in hand along one of the "rays" toward the central rotunda. The airport was crowded and I was keenly aware of the southern accents surrounding us. Pat asked me to buy more comic books. He'd finished the ones we'd brought with us. When we reached the rotunda I looked around for a book and magazine store. I spotted one almost directly opposite where we stood. Over the doorway in a decorative arc was a bright colorful array of Confederate flags. A similar array of swaztikas could not have had a more alarming effect on my nerves. I wanted to gather up my child and run back to any plane which would return us safely to New York. We went in, however, and bought 3 comic books of Pat's choice and though we got a less than enthusiastic look from the woman behind the counter, everything seemed normal. The next challenge was the small cafeteria next door. Pat was hungry and wanted a hot dog. We sat at the counter. Pat chatted as he normally did. I hoped this would not be the place for a showdown. The waitress there also seemed sullen, but took our order and in due time the hot dogs arrived. My nerves were beginning to settle down a little. The only person who stared at us, and he did so the whole two hours we wandered around the terminal, was an older black man leaning on his crutches. Once when we passed quite close by him I nodded in his direction. He smiled and nodded back. We boarded the plane and settled down for a short uneventful flight to St. Simon Island. When we landed I was startled to see we were quite a distance from the terminal. I peered anxiously through the window looking for Bill's relatives. I knew there would be three or four people, one of them Uncle Aaron. How would we recognize each other? Pat and I were easily identifiable to them. A very tall white woman about 35 with a light skinned blondish kinky haired boy who would probably be talking animatedly. But I still didn't know what they looked like other than that they were black. As we emerged from the plane at the top of a tall staircase the problem was solved. The airport terminal was a long low one story building with an overhang. Under the overhang behind a barrier stood a small group of Black people at a considerable distance from the larger group of waiting whites. Suddenly they burst out with shouts and waving hands, some even jumping up and down. "Bergie, Pat, over here, over here", they called. Somehow I had thought they would be reluctant to advertise our presence. I thought they would figure out some secretive signals to catch our attention and that we'd quietly slink off to their car and hope for the best. Not so. We were immediately enveloped in hugs and introductions. It was a noisy excited group that left the terminal and climbed into Uncle Aaron's station wagon. Uncle Aaron drove while the cousins, mostly around my age, asked question after question about New York, the trip down, had we ever been in the 'country' before and when was Bill (Junior, they called him) arriving. Pat described in detail all the buttons on the plane and what they did. We drove over the bridge from St Simon Island through the city of Brunswick south to Woodbine and beyond to the small hamlet of Scarlett. I tried to catch sight of the passing scenery. It was very green, I remember, lush. Tall grasses, fields of growing crops, interspersed with stands of trees. But most of my attention was focused within the station wagon. I would have to see the South later. What scenery I did see outside the cities was sparsely populated, beautiful, rural and serene. When we arrived at Uncle Aaron and Aunt Letha's house, the front porch was full. Children of all different sizes, dogs, and standing in the doorway behind them was the imposing Aunt Letha, clearly all waiting for us. We climbed out of the station wagon and as some of us were struggling with the suitcases, the porch people seemed quietly expectant. They stared at Pat and me. Suddenly Pat said, "Ma! Look! Chickens!!!! Everyone burst into laughter and the ice was broken. There were indeed chickens wandering all around the house pecking whatever it is they peck. After a few awkward moments of introductions, he ran off with a cluster of cousins to explore the chickens and anything else they had to show him. Pat, the New York boy, had arrived in Scarlet. Bill arrived a couple of days later and was greeted with much enthusiasm by the family who seen him just months before after many years' absence. We were settled into the front bedroom off the living room. It had a double bed, a dresser and a chair. The two windows were screened and were open all the time I was there. Pat slept in a bedroom off the dining room. The house was modest by most standards I am familiar with. The front room and the room behind it were the living room and dining room respectively. Behind that again was the kitchen. Along the left side were bedrooms. Ours led directly into the living room, the others were off a hallway from the dining room that continued to the back of the house. I don't remember if there were three or four bedrooms all together. There was no plumbing in the house. All the material and parts for plumbing were lying

I was shown where the pump was on the side of the house and how to work it. During the three weeks we were there I took my turn pumping water into pails which were brought into the house for cooking and dish-washing after each meal in readiness for the next. Clothes were washed in a washing machine on the open back porch and clothes were hung to dry on lines strung between trees. The washing machine was filled with buckets of water from the pump. While they didn't have plumbing, they did have electricity. It seemed odd to me that they had no water but could sit in front of a large color TV, had a refrigerator, lights, washing machine and other such conveniences. The refrigerator stood just inside the dining room. There was enough space between the refrigerator and the wall for a chair. I didn't notice the chair until one day there was a thunderstorm. Aunt Letha sat on that chair braced between two protecting "walls" and prayed until the thunder and lightening stopped. The outdoor privy was a little distance from the house at the end of a well-worn path. Every time Pat and I traveled that path a small hog followed us. We named him Oscar. Since neither of us had any experience with hogs he made us nervous. He looked mean. I never had the gumption to ask if he was inclined to bite. I certainly didn't try to pet him. Now I would. I understand they are very smart and quite charming. I remember Aunt Letha as a tall stout woman with a pleasant brown face. In contrast to

To the right of the house was Aunt Letha's garden. A garden to my citified mind is a place to grow flowers and sit outdoors on a pleasant day. Her "garden" was a small farm as far as I was concerned. In it grew corn, beets, beans, squash, collards, pumpkins, watermelons, just about any vegetable you could name. It was the main source of food for the house. It seemed to me that they only shopped for meats other than pork and chicken, coffee, milk (they no longer had cows), cereal, and other conveniences they couldn't or didn't grow. Aunt Letha would not accept any help in the house or the garden from me except pumping water and washing dishes occasionally. She said so little around me, I felt perhaps she didn't like my presence in her house. After we had been there awhile I told this to Bill. He told me to look at my plate at mealtimes. I didn't know what he meant. He said that my plate was piled high with more than what two people should eat. I acknowledged that and gathered from this evidence that my approval rating was high. One afternoon, after I had been there a week or so, I was sitting in one of the several rocking chairs on the front porch trying to cope with the heavy heat. Next to me Aunt Letha sat snapping beans and looking at the passing cars and trucks. I had noticed early on that the truck drivers who hauled pine trees to the pulp mill nearby, always stared at our porch as they drove by. I was surprised to note that there were both black and white drivers. Both stared. I was pretty certain that they were looking for the white woman who was staying at the Weston house. News travels fast. A truck passed with a staring driver. "If them drivers don't stop staring, they'll find themselves upside down in the ditch" muttered Aunt Letha. It was the longest sentence I remember her saying in my presence. I laughed in agreement. Uncle Sonny was Uncle Aaron's uncle, Bill's great uncle and was about 95 years old, give or take a year. It depended on who was talking, just how old he was. In any case he was born a few years after emancipation. Uncle Sonny usually sat in a rocking chair on the front porch of his spacious comfortable one- story house. His round steel rimmed glasses were almost always askew. When I had gotten to know him better I usually greeted him by taking his glasses off and straightening the rims for him. He would laugh and say that my work wouldn't last til the next time. He was right. Usually one or another relative would stop by during the day to see how he was doing and to bring food. He was well taken care of although he lived alone. One of his married daughters lived in a house at the corner of the road where his long spruce lined driveway began. Uncle Sonny and I had good chemistry and I walked the mile to his house almost every day to visit. We talked about the country around Scarlet. I asked questions somewhat based on what Bill had told me of the family background. I asked what the area was like when he was a boy and when he was a young man. He would describe the rice fields that no longer were there and that many had owned cows and horses in the old days. Now there was a fence law that put an end to that. No single person owned enough land for adequate grazing. I also asked him one day about the island where the slave traders from Savannah delivered the slaves to be sold in this part of the county. I told him that Bill had discovered in some book that they had been kept on an island in the fast rushing slough nearby. I wanted to know where that was. He looked a little surprised and then said, "Oh, you must mean "monkey island". Interesting. Bill had thought the place was called African Island. Uncle Sonny was not sure about the history of the place, but that must be where it was. The water was too fast around the island for any slave to escape. I wondered aloud if there were any artifacts left there, if one dug for them. Uncle Sonny shook his head and said, "I don't think there ever was much out there even in the old days. You don't want to go out there, anyway. Lots of snakes. Poisonous ones. Have to go out there in a boat with a shotgun. Do you know how to shoot?" I had to admit not. Later I asked a young cousin of Bill's about the island. He knew where it was. He agreed with Uncle Sonny. But he said there was an old white man who fished near there and he would probably take me out. He also had a shotgun. Nope, I didn't think I was that curious. It would have to wait for someone braver than I. I think it was the old white man who made me more nervous than the snakes. Uncle Sonny's sister (Bill's grandmother) Harriett was a slave until she was about 12 years old. Bill and I went to visit what was left of her house deep in the lush semi-tropical growth. A brick chimney and a small part of the foundation was still there. Slavery seemed very close by in Scarlet, Georgia. Everyone I met owned their land. The history of Camden County Georgia reveals that for 12 miles on either side of the St. Mary's River was given to the newly emancipated slaves at the conclusion of the Civil War. Much of the land was still in the hands of their descendants at the time of our visit. That piece of information was the key to understanding the relative independence of the Black population in the area from white problems. Bill remembered stories of Uncle Sonny in his youth being a horse trader. Any whites who came into the Scarlet area looking to buy or sell horses had to deal through Uncle Sonny. He apparently cut a dashing figure on horseback in those days. Besides being the patriarch of the community, he knew how to read, write and count. None of the Blacks would buy or sell without Uncle Sonny checking the transaction. A mutual respect of sorts existed between the black and white communities. Segregation, however, still reigned. One day I was making the bed in our front bedroom. A truck pulled up out front. I stood looking out from the screened window as a white man got out. It was a mattress salesman judging by the advertising on his truck. I went quickly to the back porch where Aunt Letha was washing clothes. "There's a white man coming up the path," I said. "I think he is a mattress salesman", I told her. "All right, I'll be right there" she answered. I went back to the bedroom and listened at the open screened window. "Good Mornin', Auntie, how are you this fine day?" There was a long pause. "Ahm doing just fine, Uncle" Aunt Letha replied. Yes! I said silently to myself. If there was going to be an "Auntie" there would be have to be an Uncletoo. Aunt Letha was not in the market for a mattress The encounter ended pleasantly enough and the mattress salesman went on his way. Most mornings of my stay Pat went off with one or another or a dozen of his cousins in the company of an adult. Bill went off in his car searching for material for the history of Camden county. He interviewed neighbors, went to the library and to the court house in search of material for his research. Sometimes I went where Pat was going and other times I walked the main road (dirt) to visit with Uncle Sonny. If not him, then I'd stop at one of the relatives or friends of the family who lived along the way. Pearl Forcine was one particular friend I liked to stop and chat with. She came from another part of Georgia. Peach country, she said. She and her husband had built a fine home and had several children. But usually I headed for Uncle Sonny's. One of the first days I ventured down the road alone, I took off my sandals as they would quickly fill with the soft powdery light brown dirt of the road and feel lumpy and uncomfortable. Under bare feet the road felt like velvet. From a screened-in porch of one of the neighboring houses came a voice, "What? City girls walk barefoot?!" "Of course we do," I countered. "At least when the dirt is this soft". "C'mon up and visit", I was invited. So I walked up the steps to the porch. Three women I had met the day before at church were sitting snapping beans. They asked what almost everyone asked while I was there. "How do you like it out here in the country?" I told them I liked it fine and that if I was going to sit here I might as well snap some beans too. "What?" It came again. "City girls can snap beans?" "Sure" I said, "if someone will show me how" and they laughed. And they showed me how. The day after Bill arrived from New York it was Sunday and a special Sunday at that. "Association Sunday" happens once a year and is the time of reunions. Hopefully everyone who was ever associated with this particular Abyssinian Baptist church would return for the reunion. Some came from Florida, others from as far away as New York! Several pastors were lined up to preach from early morning to late in the evening. There were breaks during which people could go outside and socialize, eat and even go home. Some returned for a later sermon, some didn't. Bill and I arrived at the church about 10 a.m. on that hot humid morning. As we approached the door of the small cinderblock church we could hear that a sermon was in progress. "Go on in", Bill gestured at the open door. "I'm going in back to take some photographs." "I'm not going in alone", I protested. But at that moment an usher looked out and motioned for me to come in, just as Bill disappeared around the corner. I whispered that I would like to stay in back, standing if necessary. Inside it was even hotter than outdoors. Fans were working furiously throughout the congregation. Suddenly the preacher stopped and everyone stood to sing. It must have been then that the word went up to the third row from the front. As people sat down two people turned and motioned to me to join them. They were friends of Bill's whom I had met the night before. We'd been there for a delicious dinner and had had a very good time. There was nothing to do but walk down the center aisle as the whole congregation watched. I felt very tall. I felt very white. I slipped in beside the couple and smiled weakly. Beverly patted my hand and whispered that she was glad I had come. Next Uncle Aaron, head deacon of the church, stood at the podium. He thanked the previous pastor for his inspiring message. He thanked the women's group for the beautiful flowers, another group for the superb food preparations and the men's group for something else. He then introduced the next speaker who had traveled all the way from St. Augustine, Florida to speak to us that day. After the introduction he continued, "Now so that everyone can concentrate on Pastor Williams' message, I want to introduce the white lady in the third row. She is my nephew's wife visiting from New York City. She is a school teacher there and I want you to welcome her to our community." People nodded and smiled in my direction. I felt my face redden from something more than the heat. Pastor Williams was a welcome relief from the attention. I could turn my thoughts to this small cinder block building, crowded with African Americans listening to "the word" and singing beautiful hymns, old old ones and some I had never heard. The intricacies of the rythms, the harmonies and rising cadences were overwhelming. 'This, right here, is where Black music began', I thought to myself. Not an original thought, but it took on new meaning for me. I also felt a cruel history surround me as the hymn came to a close. When it was time for a break, I walked out with Bill's friends and family. He was nowhere to be seen. (I don't think he had ever intended to going into the church.) People from the congregation began to come up to me one by one, as if I were on a reception line, to express hope that I would have a good visit in Scarlett and to say that they were so pleased I had come to the church. I was getting close to tears when someone said it was time to go home. It was late that evening before the sounds of the crickets replaced the sounds of hymns in my head. The next day was hot and humid as usual. The telephone rang. I was the only adult in the house, so I answered it. It was cousin Dorothy. "Two convicts have escaped the county chain gang and may be headed your way. Just heard it over the radio". "What do you think I should I do?" I asked her. I didn't have any experience with chain gang escapees. "Pat and Marcus are here with me. Every one else is gone" I added. "Stay inside, lock the doors and windows" she answered and hung up. She had others to call and didn't have time to waste. Lock the doors and windows? I wondered if they had ever been locked. The house was full of windows, all open and screened. I tried one and it wouldn't close, never mind lock. I sat down to think. If two escapees, men, came here… I knew immediately that I didn't want to be here. Nope, we would go out. But then I remembered that there were three or four shot guns behind the open kitchen door. I suddenly remembered the movie "The Defiant Ones" starring Sidney Poitier and Tony Curtis, about two chain gang escapees, one black and one white who were chained together and hated each other's guts. When they approached a farmhouse they wanted a change of clothes, food and they wanted a gun to shoot the chains that bound them. Aha. I knew what to do. I didn't care if they got clothes and food, but I did not want them wandering around with guns. So armed with my motion picture expertise I gathered the shot guns ( I had never touched one before) and hauled them to the back-most bedroom and hid them under one of the two beds I found in there. Then I took the two boys to the swimming hole and hoped there were no snakes in it today. The convicts were caught within the hour somewhere else in the county and I was vaguely disappointed. I didn't hear about it until that evening when some of the family gathered on Uncle Aaron's porch. Suddenly I remembered the guns. "Oh, I almost forgot. I hid the shot guns under the bed in the back bedroom when I heard about the convicts." That brought a roar of laughter. That is not what country folk would have done, I gathered. Over the next few days the story was passed around and I was royally teased. I began to mutter to myself that it really was the smart thing to do since I didn't know how to shoot. But somehow I knew I would never convince anyone of that. Another day Cousin Dorothy called again. It was fine day for fishing. So several cars were packed with fishing gear and off we went. Adults and children all piled out of the cars near the St. Mary's river. In order to get to the river we walked along a path through tall grasses on private property belonging to wealthy white people. The house was closed up for the summer. "They don't mind our trespassing", said Dorothy in response to my nervous questions. On the banks of the river we set up camp with food and drink in coolers and fishing gear laid out. We fixed and fiddled with our fishing poles and began to bait our hooks. That is, they began to bait their hooks. I watched closely to see how it was done. Then I reached into the pail of worms and took one squirming worm between my fingers in a determined fashion. "You mean a city girl can bait a hook?" someone asked, grinning. "You betcha" said I, just as the damned worm wiggled out of my grasp. There was laughter as Cousin Bertha picked it up and showed me, up close, the best method of skewering the worm. I actually got pretty good at it, but didn't catch a single fish that day. The visit to Scarlett came to an end. We went twice to Georgia. Some of what I have written here happened on the second trip in 1970. The memories blend. The main difference between the two was that on the second trip I was full of happy anticipation instead of fear. On the second trip I knew also that during the visit we would talk far more about the differences between city and country living than about the differences between black and white. City Hall Demonstration| Previous page |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

HOME | My Friend Sanora | Les Deux Megots | The First Demonstration

March On Washington | It's Hard To Know | City Hall Demonstration

| Georgia |