This is the prologue to the book “Down Home: My Return to the Georgia Backwoods” written by my father early 1970’s. The book is an exploration of the area in rural Georgia that he grew up in and how it changed in the 50 years since he was born there, especially focusing on the history of local Blacks in the community. He wasn’t able to get the book published at the time, but his work on the book led to his career as a history professor. I self-published the book in 2004 about 9 months before he passed away and recently published the second edition. The full book is available here.

I’m a stranger here; jes blowed in yo’ town

I’m a stranger here; jes blowed in yo’ town

An’ because I’m a stranger, everybody dogs me ’round.

I wonder why people treat a po’ stranger so?……

‘Cause you know everybody got to reap what they sow.

I’m goin’ back South – if I wear out ninety-nine pair ‘o’ shoes……

Where I know I’ll be welcome; an’ I won’ have these stranger blues.

– STRANGER BLUES

by Hudson “Tampa Red” Whitaker,

Georgia Blues Singer and Guitarist

THE HOMECOMING

“A’ ant is a small thing, but if you mash it you fin’ de gut!”

This phrase I heard often from my grandmother, Harriett Weston, years ago when I was a small boy. She owned a farm in Camden County near the southeast end of coastal Georgia. The meaning of the expression varied according to the circumstance in which it was used. Sometimes it signaled her intent to get at the root of some problem; she also used it as an explanation of how she had solved a problem; again, it might constitute a cryptic denial of some request that she had no intention of granting. In other words, it was one of her favorite expressions.

The two of us lived alone on that farm for many years, during which I had countless opportunities to witness firsthand many other examples of her unusual wit and intelligence. The amazing thing to me about all of this was the fact that grandma was totally illiterate! She was born in 1857 on a plantation only five miles away and spent the first eight years of her life in slavery. Her entire life was spent within a radius of 100 miles of the place where she was born. Nevertheless, she possessed all the mental and physical skills necessary for survival within the confines of her limited world. At no time since have I met anyone possessed of a more analytical mind than this backwoods peasant woman.

I had occasion to recall that phrase many times when I returned to this backwoods area for the sole purpose of a brief visit but, as a result, found myself searching for the “guts” of its history. I had been in self-exile and had maintained little contact, personal or otherwise, with anyone in the area. Except for the occasional news of someone’s death conveyed in passing by some relative or acquaintance from the vicinity, I had been completely isolated from the land of my origin. This isolation had not been accidental: for, like many other Southern Blacks of my generation, I had pulled “up stakes” and left for the “promised land” vowing never to look in a southerly direction if I could avoid it — let alone return.

For nearly 30 years I kept that vow, at least insofar as it pertained to my native soil. The credit for my decision to break this vow and consider returning home after all those years must go to my young son, Patrice. Although increasingly as I grew older, thoughts of home crossed my mind, I had not considered going back. However, as my son approached his sixth birthday, the questions — as they inevitably must — began to come: “Hey Dad! Where were you born?” “What did you do when you were growing up?” “What was it like living on a farm?” “What was your grandmother like?” “Why did you leave and how come you never went back — not even once?” And on and on — ad infinitum.

The more questions he asked, the more my mind began to dwell on home. Why not go back? Wonder how many of the old folks are still alive? Is the old homestead still there and, if so, is anyone living on it? What’s the matter, are you afraid to go back, afraid of what you might find? After all, its home, that’s where your roots are. The clincher came when one day my son said to me, “Hey Dad, I’ve got an idea: Why don’t you and me take the car and drive down to Georgia? I’d like to see the place where you grew up and meet our family who still live there.” That did it! I resolved that at the first opportunity I would pay a visit “down home” and renew acquaintance with my past.

In May of 1969, having first supplied myself with enough film and tape to photograph and record most of the inhabitants of the southeastern United States, I headed my car south and set out on my journey of rediscovery. I timed the beginning of my trip so that the daylight hours would be spent driving through the South. This would afford me the opportunity of photographing people, places and things of interest I encountered along the way. After leaving New York around midnight and driving the rest of the night, I arrived in upper Virginia just before daybreak the next morning.

After stopping at a motel to wash up and have breakfast, I hit the road again. Before midmorning I was driving through the lush countryside of North Carolina, the land of my father’s ancestors. The planting season was in full swing, and as I went by, people working in the fields or walking along the road would wave to me and smile in greeting. Once I passed an old black man driving a team of oxen pulling an ox cart. He seemed to be in his mid-eighties and was sitting with both legs hanging down on one side of the harness shaft with all the aplomb of a monarch on his throne.

The contrasts between the old and new were sometimes stark. In a field on one side of the highway men were plowing with the latest mechanical implements, while in another on the opposite side, other men could be seen following mules pulling old-fashioned hand plows in the same manner as their grandfathers had tilled the soil. On some fields mechanical seeders using tractor power were in use; in others, groups of black women, stooping so low that their faces seemed but a few inches from the ground, sowed seed by hand! There they were — two antithetical systems of agriculture — co-existing side by side and, seemingly, in complete harmony! The examples serve as effectively as any I know to illustrate the extreme diversity of attitudes and philosophies that somehow manage to exist alongside each other in the South.

As I barreled along Interstate Route I-95 at a seventy-mile-per-hour clip, I gradually became aware of a growing sense of anticipation and excitement welling up within me. I had originally planned to take about two and a half days to complete this trip. Since I was traveling alone and had no one to assist with the driving, I didn’t want to push too hard and tire myself out in the process. The distance from New York City to my destination, Woodbine, Georgia, is approximately a thousand miles.

As the sense of anticipation grew, however, I began to feel the urge to get “home” as quickly as possible. Accordingly, I decided to cut my traveling time to a day and a half. By this time, I had been on the road for about twelve hours straight and was as yet feeling no signs of fatigue — my sense of excitement was too high.

Upon entering Virginia earlier that morning I had felt that sense of apprehension which all black Southerners must develop if they hope to survive in their homeland. It is a sense that must be acquired early in life and sharpened to the point where it reacts like an extra reflex muscle. Its presence can often spell the difference between life and death. One’s education in acquiring this “extra sense” is speeded up considerably by the actions and admonitions of one’s family and community. Furthermore, each “lesson” must be absorbed instantly; there just isn’t time for repeats or refresher courses. One either learns immediately, or suffers the consequences!

Since no human being can be expected to live in a state of constant anxiety, it is necessary to acquire the ability to switch one’s “apprehension light” as required. To trigger this control most Southern Blacks develop sets of invisible “feelers” which not only activate the “circuit” but also give advance information concerning the type and degree of apprehension to be felt, along with an indication of the kind of emotional reaction called for. When not in use, these antennae retract themselves somewhere in the psyche and lie passively until they are required to spring forth again to pick up danger signals.

It is not sufficient just to acquire a general sense of apprehension; it is essential to subdivide it into various categories so that one’s response may be exercised only to the extent necessary — no more, no less! Hence, a Southern black usually carries with him at all times, as part of his emotional luggage, a whole series of apprehensions, labeled according to type and ready to be brought into play as the occasion demands.

Sorting these apprehensions is no easy task; some types are so closely related as to almost overlap. Still, the distinctions must be recognized and responded to accordingly. Two of the common types may be labeled as: “local apprehensions” and “traveling apprehensions”. An example of how the first category is applied is the different ways in which Southern Blacks may react to being addressed as “boy” by a white person. The reaction may range all the way from annoyance to anger or fear, depending upon the degree and type of hostility that the antennae may “sense” in the addressor. This “sensing” may have absolutely nothing to do with whether obvious hostility is indicated by action or tone of voice; the “sensing” is done on a deeper, almost instinctive level. If the black misinterprets or chooses to ignore the apprehensive intelligence relayed by his antennae, he does so at his peril!

The second category comes into play whenever a black person (Northern or Southern) travels in the South. The antennae first alert him to the fact that he is not only in strange, but also hostile territory. Then the secondary “apprehension activators” take over; they remind him to be on guard against sheriffs and state troopers saddling him with speeding tickets unjustly (keep speed at least ten miles below the legal limit if possible). They warn him to bend every effort to avoid getting involved in accidents — regardless of who is at fault — with Whites, especially women (maintain as much distance as possible between you and any other vehicle). They help him anticipate possible trouble spots when stopping for food, gas, repairs or lodging (this restaurant doesn’t appear too inviting — too many rednecks hanging around — drive on to the next one). The traveler rarely relaxes until he is back on familiar ground.

It was my “traveling apprehension” that had come into focus when I crossed into Virginia that morning. In fact, my antennae were far more sensitive than normal. Having been away for so long, my “Southern apprehensions” were quite rusty and needed a strong dose of extra stimulation to oil them up again. That is not to say that New York Blacks don’t have apprehensions, they do; but “Northern apprehensions” are a different breed from their Southern counterparts; therefore, different emotional techniques must be used in order to perfect them. Having spent over thirty years trying to cope with the New York variety, I was unable to shift gears smoothly and ease back into the Southern version without some strain. Thus, in the beginning, I overreacted.

Once or twice while driving through Virginia I considered turning back. “What the hell am I doing?” I’d ask myself. “Why in hell am I out here on a strange highway that probably leads to nowhere, trying to find my way back in time to a place which, for all I know, may no longer exist? Hadn’t Thomas Wolfe, and others who tried it, said, ‘You can’t go home again.’? Thirty years is a long time. The old people are probably all dead; the young ones won’t know me. I’ll probably wind up standing in the middle of some crossroads, surrounded by strangers, feeling like a damned idiot!”

I even considered going back to Baltimore, where I had friends, spending the night with them and then taking off for Brooklyn the next morning. (I had not told anyone in Georgia that I was coming. I’d told my wife that the reason was that I wanted to surprise them. This was only partly true; I also wanted to be in a position to turn around and come back in case I chickened out, without anyone down there being aware of it!) However, by the time I reached North Carolina my spirits were all charged up and I gave little thought to the idea of turning back. Besides, by this time, I had cut the distance almost in half and it would take about as much time to get back to Brooklyn as to continue on to my destination. It would certainly be stupid of me to turn back at this point and announce to my wife that I had gone half way and then gotten a bad case of cold feet.

It was a balmy spring day and the soft fragrance of honeysuckle was mixed with the pleasing odor of freshly turned earth. As I drove along, my imagination began to peel away the layers of years and soon I became deeply engrossed in remembrance of things past. Once again, I was a carefree boy tramping barefoot through the woods. In my mind’s eye I took in the entire expanse of grandma’s farm. I saw all the buildings: barn, henhouse, smokehouse, dairy and syrup house. I saw the road that led up to the broad expanse in front of our house which, for some reason, we called “the lane”.

I could see all our utility buildings arranged on both sides of “the lane” and the huge woodpile (which one of my chores had been to keep supplied from the forest) placed almost in the center. As nostalgia took full possession of me, I began to flesh out the rest of that farm: the grape arbor, the rice field down in the bottomland that grandma had cleared of trees and undergrowth all by herself while grandpa cleared the other farmland. She was determined to grow rice without delay, so she had prepared all ten acres single-handedly. I remembered how in later years when I’d asked her how she’d done it, she answered, “If you git up an’ try to he’p yo’se’f, then God he fin’ a way to he’p you. If you sit on yo’ behin’ an’ wait fo’ somethin’ to fall in yo’ lap, you starve to death! Lazy folks don’ never git nothin’, even de bird in de fiel’ got to work fo’ his food. You do nothin’, you git nothin’, tha’s all dey is to it!”

Now, riding along thinking of the past, I had an overwhelming urge to get home as quickly as possible. I told myself that the first order of business when I arrived would be to pay a visit to the old homestead. Looking at my watch, I noted that it was only eleven thirty. I decided that I would cover as much ground as possible before calling it a day so as to arrive early the next morning. My apprehensions were all gone now, all I though about was getting home.

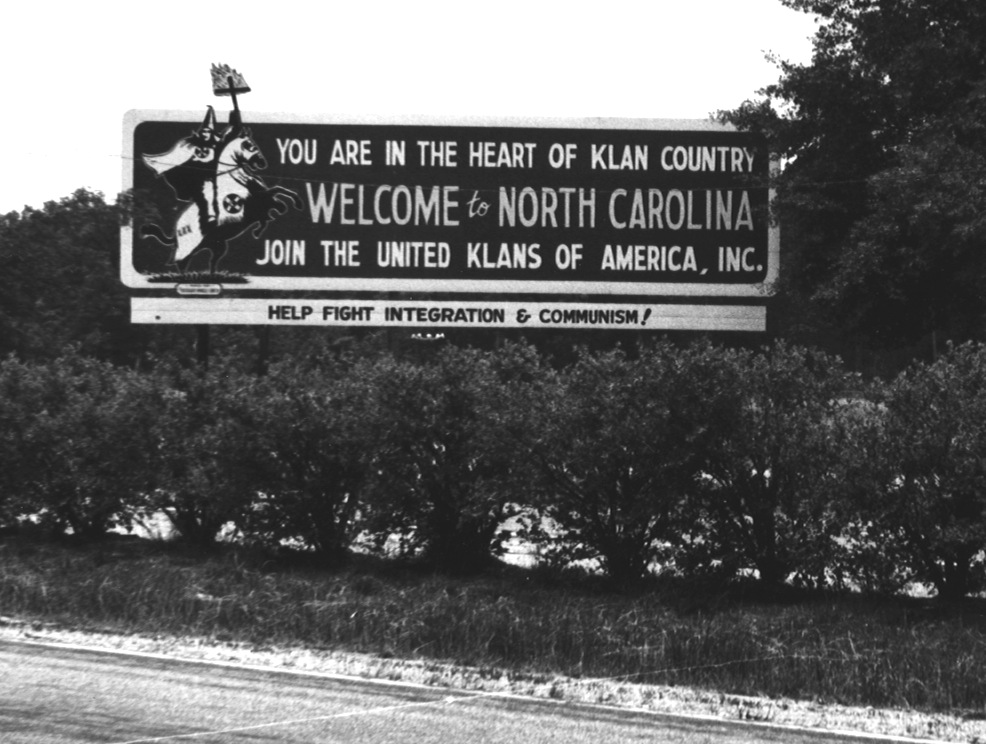

Then, as I was nearing the town of Wilson, North Carolina, I came around a curve, and there it was! Just off the highway on my right stood a huge sign painted red and blue with white letters. In the left hand corner was the figure of a knight clad in white armor and mounted on a rearing horse. At first glance I thought it was some kind of ad for “Ajax Cleanser”, but upon looking closer, I saw that nothing could be further from the truth. When the full impact of what that sign said hit me, I almost ran off the road! This “white knight” was clad in the regalia of the Ku Klux Klan, complete with symbolic “K” emblazoned on the horse’s blanket. His head was covered with the traditional pillowcase, which had a cross painted on it in the places his eyes and nose would normally occupy. In his upraised left hand he carried a burning torch that projected about eighteen inches above the top of the sign proper. The horse was entirely black (which fact I suppose can be construed as representing a kind of ironic symbol in itself if one wishes to stretch the point.) In his right hand the “knight” was carrying what appeared to be a bible. The legend on the sign, in heavy type, about twelve inches high, read:

YOU ARE NOW IN KLAN COUNTRY

WELCOME TO NORTH CAROLINA

JOIN THE UNITED KLANS OF AMERICA, INC.

Below the bottom of the main sign, as if tacked on as an afterthought, a piece of board, about eight inches high, was attached. The message was:

HELP FIGHT INTEGRATION AND COMMUNISM

In case some sympathizer was compelled, for any reason, to limit himself to resisting only one of the two evils, it was obvious from this sign, which one the Klan gave top priority.

Having pulled over on the shoulder of the highway and stopped, I sat there for about five minutes gazing at that sign in wonder. There it stood — hard by a Federal highway! Suddenly I had a nagging feeling that maybe somebody was trying to get a message over to me! I became aware that my old friend, “apprehension”, was beginning to tug at my guts once again. With some effort, I managed to push my anxiety way down into the inner recesses of my mind. I pulled back onto the highway and continued on my way. “Hell”, I muttered, “it’s too damned late to turn back now”.

Just the same, the image of that sign remained imprinted on my consciousness for quite some time afterwards. I tried consoling myself with the rational that this was the South and one could expect to see almost anything along the highway. After all, “Southern Hospitality” was one of the major assets the South was constantly boasting about. Quite possibly, one aspect of this “hospitality” was the granting of permission to anyone so inclined to install signs in conspicuous places near major highways for the purpose of promoting any message or philosophy they saw fit. It occurred to me that maybe further on I might encounter a sign espousing the cause of the Black Panther Party.

Such an eventuality would serve as proof positive that the concept of “equal time” had been extended from the narrow confines of the broadcast studios to cover the lengths and breadths of our major highways! But, alas, it was not to be. Not only were there no billboards extolling the virtues of the Panthers, I didn’t even see one that took up the cudgel for a middle-of-the-road group such as the Americans for Democratic Action.

During the rest of my journey I saw many signs advising the impeachment of Chief Justice Earl Warren. And there were two that went for broke and recommended sacking the entire United States Supreme Court!

The number of this type of political sign increased as I penetrated deeper into the bowels of the Southland. In addition, their language grew more and more strident. The second most numerous category of sign was those with a religious bent. They usually confined themselves to warning the traveler to repent and ask forgiveness for his sins immediately, as Armageddon was imminent! After a while, I almost expected to see a miniature chapel standing next to them, complete with Bible and resident minister to administer personal absolution to any traveler who had been properly primed by reading all the signs of similar nature that he had encountered before. With all the billboards that frequently cautioned him against political devils on one hand, and the ones that cautioned him against supernatural ones on the other, the unwary voyager found himself trapped between two extremes — a Scylla and Charybdis of the open road.

By early afternoon, I found myself in lower North Carolina. Now I was in more familiar territory. This was a section I had known well from having worked there when, as a youth, I had been employed by the Seaboard Air Line Railroad Company on one of its “extra gang” crews. I was traveling much nearer the coast than before and the terrain reflected this change. The land was much flatter than before and, as a result, there were miles and miles of monotonous sameness. This is the heart of the North Carolina “black belt” plantation country.

The people in this part of the state appeared much poorer than those I had seen in the upper, more industrial part. The number of inhabited shacks per mile increased the farther south I drove. Even the continuity of the superhighway was broken. I was forced to make constant detours getting on and off the bits and pieces of I-95 that seemed to have been scattered about at random in chunks varying from about ten to seventy miles in length.

The main reason for all these detours (I was told by various people whom I questioned on the subject) was that the poorer counties in North Carolina, South Carolina and Georgia had been unable to come up with their assigned quota of these states’ contributions to the Federal Highway Program. (I discovered later that only ten miles of Interstate 95 had been completed in the entire state of Georgia). For about three hours, I spent so much time getting on and off this maze of truncated highway that I began to feel like an updated Minotaur, part man — part car, trying to fathom an al fresco version of the Cretan labyrinth!

One of the side effects of all these detours was a slowing down of my rate of travel. Many times I was forced to take directions that were at right angles to the one in which I wished to go — south. Sometimes I went as much as twelve miles east or west before making a southerly connection again. In addition, the alternate routes invariably went right through the center of towns and villages along their paths instead of bypassing them as the superhighway does. In many cases, this necessitated slowing down to speeds of as little as five miles per hour. Although there was some compensation in the fact that these routes gave me an opportunity to see considerably more of the people and their environment than was possible on I-95, this was offset by my impatience to get home.

In the end, the “alternate” routes had the last word. For somewhere in the lower half of South Carolina, after the last, long, dying gasp of about sixty miles, I-95 gave up the ghost and just quit altogether. That was the last I saw of it until just before turning off Route U.S. 17 at the end of my journey. There a sign informed me that only seventeen miles distant (just across the border in Florida) I-95 would pick up again and continue on uninterrupted for two hundred and fifty miles, all the way to the Florida “gold coast”. This bit of helpful information left me, to say the least, somewhat less than ecstatic. It would have been of considerably more help to me had that two hundred and fifty mile segment been stretched out over the last part of the distance I had just completed. It lacked only about sixty miles of being as long as the ground covered since I had last seen it (about three hundred and ten miles).

After leaving I-95 for good near Marion, South Carolina, I continued south via U.S. 301 as far as Summerton, South Carolina where it merged with U.S. 15. Since U.S. 15 split itself into two directions at this point and the indications as to which one goes south were not entirely clear, I decided to stop at a restaurant which occupied the apex of the split for directions and a short rest.

While eating a sandwich and getting directions from the counterman, a white man of about 35 years of age, dressed in the uniform of a Master Sergeant of the U.S. Army, sitting on the stool next to me, turned and asked how far south I was going. His speech had that drawl so characteristic of Whites of the deep South. I answered that I was going almost all the way across the state of Georgia to within fifteen miles of the Florida border. He said he was headed for Midway, Georgia and asked if he might ride that far with me if I had room.

For a moment, listening to that drawl, I hesitated. Then I thought: “What the hell, what harm could it do?” Besides, I had been alone for so long that a little company might be good for a change. It would also help to keep me alert. I told him I wouldn’t mind having someone to talk to for a change and that he was welcome to a ride. He thanked me, then offered to share gas expenses with me as he had money and fully expected to pay his way. He even offered to pay for my meal but I refused. After having the car checked and the tank filled, we hit the road.

For about the first ten minutes after we started, neither of us said anything. We were too busy feeling each other out. Finally, he broke the ice by asking where exactly in Georgia I was going. When I told him, he said he’d never heard of it. I said that it was a hundred and ten miles south of Savannah, and that the fact that he had never heard of Woodbine was not surprising, since it was so small that it would take no more than two minutes to drive through it at two miles per hour. “At least that was its size when I left”, I added. “As a matter of fact”, I said, “come to think of it, I’ve never heard of Midway before either”. We had a good laugh at this.

I asked how long had he been in the Army and why had he chosen this method of travel to come home. He said that he’d joined up when he was twenty and bored with life in Midway where he was born and raised. He thought joining the Army would be the quickest and easiest way to see some of the rest of the world, so, he’d enlisted. In the beginning, he intended making a career of it but, now, after fifteen years, he’d become disillusioned and quit. He had suffered a severe stomach wound about a year and a half ago in Viet Nam and had been hospitalized for over a year. (As he was talking he pulled the bottoms of his shirt and undershirt out of his pants and revealed a wicked looking, jagged scar about five inches long running horizontally across the center of his navel!)

While lying there in that hospital, he went on, he had plenty of time to think and be scared. The war had long since ceased to make any sense to him, and he began to wonder if there had ever been any logical reason for our being there. He said it had been obvious to him for a long time that all the Vietnamese, north and south, hated our guts. It was his opinion that the only Vietnamese who liked Americans were the ones who profited from our being there. And even they only tolerated us.

About six months ago he’d been brought stateside and placed in a convalescent hospital near Boston and had been there until three weeks ago when he was released as being completely recovered. Upon being given his choice of reenlisting for limited duty or resigning, he took the latter course. After spending the last three weeks visiting various cities in the northeast and trying to make up his mind about his future, he had come to the conclusion that the best place for him was back home in Midway, Georgia. At the last minute he’d decided, just for the hell of it, to hitchhike back and see some of the country along the way. He had been on the road for five days now and was lad that the end of his journey was in sight.

He asked me how long I had been away and when I told him, his eyebrows went up. “Man, that’s a long time”, he said. “Y’all left just about the time that I was being born!” He asked why I hadn’t come back to visit before now. I just looked at him and laughed. He looked down at his lap for a moment, as is in deep thought, then said quietly, “Oh yeah, I forgot”.

We rode in silence for a long while, each involved in his private thoughts. Finally, looking at his watch, he said, “Damn if we ain’t making good time considerin’ these li’l ol’ one-lane roads we been on most of the time”. I nodded in agreement, keeping my eyes on the road ahead. I was determined not to get involved in any kind of discussion on the relative merits of the ‘good life’ Southern style. I had heard them all many times, years ago, and had no desire to have them enumerated for my edification once again. Neither was I interested in hearing him extol the virtues of any ‘ol’ black mammies’ he many have had, or about the good times he may have enjoyed playing with the sons of his family’s darkie washerwomen’ in his youth. In other words, my ‘Southern apprehensions’ were on the alert again! Therefore, I resolved not to leave any opening that he might slip through and sneak up on me in a flank attack.

I was so busy thinking about how to ward off any assault on my inscrutability, that I was totally unprepared for what came next. “You know”, he said, “things have changed a lot for the better for y’all down heah in the last few years. They ain’t changed enough — but it sho’ is a lot better’n before. An’ more change is comin’ all the time. Even in the Army, things is changin’ fast. ‘Course, I realize that for folks who is sufferin’ from the loss of their dignity, things don’ ever change fast enough! But they is changin’ all right, yessir. Now, you take the Army — it don’ even look like the same Army I joined fifteen years ago. All different now. See more o’ y’all gittin’ promoted all the time; more non-coms, more officers — more everythin’; To tell the truth, I cain’t hardly keep up with some o’ them changes. Gits kinda confusin’ to me sometime, too. Man, it took me the longest time to learn how to say ‘Negro’ instead of ‘Nigger’. I never meant no harm in sayin’ ‘Nigger’ — it just growed up in me — that’s all I ever heard ‘roun’ home! Man, I used to git in some fights over that word! But I learned!”

“It seemed like almost as soon as I got ‘Negro’ down pat — y’all wanted to be called somethin’ else — ‘Afro-American’. Now the word is ‘Black’. Yessir, it sho’ is confusin’ sometime. Still, I guess everybody ought to have the right to say what they want to be called — don’ matter how many times they change it. It’s their right! Now, take me. Anybody who call me a Georgia Cracker better be ready to fight! Man, I wish I had a dollar for every fight I had ’bout that word; I’d be a rich man now. An’ sometime I was called ‘Cracker’ by black soldiers who was ready to kill me if I called them ‘Nigger’. Kinda crazy, ain’t it?” I nodded my head and kept silent.

One thing was quite clear, he was not trying to con me, he was obviously sincere about the things he had just said. Occasionally, while he was talking, I glanced at him surreptitiously out of the corner of my eye. At no time was he looking in my direction, but seemed to be concentrating on some fixed point, way off somewhere in space. In fact, it could easily have been assumed, from his general attitude and manner of speaking, that he was not talking to me at all. He sounded as though he was in the process of trying to grasp the discrete elements of some strange, but fascinating, theory he’d discovered and was using me as a convenient sounding board to bounce them off in an attempt to make them coherent.

It was obvious that his Army experiences had had a profound effect on him. And I couldn’t help wondering how these experiences would affect his efforts to readjust to the mores and attitudes of a small Deep-South town. It would be interesting, I thought, to come back and talk with him five years from now to find out what had happened to him in the interim.

We had picked up U.S. 17 at Walterboro, South Carolina, and were traveling closer to the marshlands of the coast. Most of this highway is of the one-land variety and, therefore, demanded an extremely high degree of alertness on the part of the motorist. There are long stretches of winding curves that meander in and out of the swampland in the road’s desperate efforts to cling to the relatively few patches of high ground that exist. The line of vision is severely restricted by the lush foliage of trees that skirt the road on both sides and the thick Spanish moss that dangles down over the highway from overhanging branches of the live oaks that abound in this part of the country.

My companion had fallen asleep shortly after our last bit of conversation and was now slumbering peacefully. His head was tilted slightly backward and his cap had fallen off, revealing a shock of the reddest hair I had ever seen. He was a rather good-looking chap of about six feet in height and weighed about a hundred and ninety pounds. He had a rather long face with a Roman nose and high cheekbones. His mouth (which was now open) was of medium width, and his lips were quite thin. His teeth (what I could see of them) were almost perfectly even. The only things that prevented him from falling into that category known as ‘handsome’ (Caucasian style) were his ears. They were about a half size too large in proportion to the rest of his facial features. They were of that type that used to be known in the backwoods as ‘flop ears’. His eyes were deep grey with many fine laugh crinkles in their corners. A ‘widow’s peak’ at the center of his forehead capped off the portrait.

He slept for about two hours during which we covered most of the distance from Walterboro to Hardeeville, South Carolina. Finally, as I pulled into a filling station for gas and a car-check, he woke up. “Where are we?” he asked. “About twenty miles north of Hardeeville”, I replied. “Damn good time”, he muttered, half to himself, “Yessir, damn good time”. I agreed that we had covered quite a bit of territory since he fell asleep. “Well, it wont be long now”, he continued, “before I’ll be back home. Lessee now, it’s almos’ four o’clock. What y’all say we git something to eat in Hardeeville, I’m payin.” I said that was just fine with me. After washing up, we hit the road again.

“There’s a Holiday Inn jus’ the other side o’ Hardeeville. Man, they got some o’ the bes’ fried chicken anywhere in the South. An’ that’s sayin’ somethin’!” His eyes widened at the pleasure of anticipation as he extolled the culinary delights fo this particular inn. “An’ the corn fritters they serve are out o’ this worl’! Man, they melt in yo’ mouth–an’ that’s a fac’!” He went on, “Y’all wanta try it?”, he asked. “why not?” I replied, “I’m game.”

In a short while, we had passed through the town of Hardeeville and soon reached the inn he’d spoken about. It was located at the Southern end of the town and had a large swimming pool that occupied a good deal of the space behind it. There was a large group of bathers sunning themselves around its borders and I noted that all of them were white. Some of them watched us with idle curiosity as we entered the restaurant. My companion, noting their looks, remarked: “Damn, you’d think they would a been used to it by now”. He stopped, then stood there about a full minute watching the watchers and laughing. Then, turning to me, he said, “Hell, come on, lets eat, I’m hungry.”

The food was just as good as he’d predicted. The chicken was superb and the corn fritters were in a class by themselves! I had eaten about six of them before I was even aware of my gluttony. Almost before I had finished them the waitress came over with a fresh supply. “I see y’all like our fritters”, she beamed. “They’re fit for a king”, I said. “Eat all y’all want”, she urged. “We got plenty more, ain’t no extra charge for ’em”. I needed no added inducement and before I quit, I had consumed an even dozen!

After having stuffed myself with chicken and corn fritters, I had very little room left for dessert and decided to pass it up. Our entire bill (including the tip) for this feast, came to only five dollars and seventy-five cents! I made a mental note to time any future trips in such a way as to have at least one meal in this inn.

As he was paying the bill, it suddenly dawned on me that we had been traveling together for over four hours and did not know each other’s names. When I pointed this fact out to him, he laughed and exclaimed: “Well, I’ll be damned if that ain’t the truth!” He stuck out his hand across the table toward me. “My name is Roy Willis, but everybody calls me ‘Buzz’, I don’t know why, but far back as I remember, that’s the name I been answerin’ to”. We shook hands and I told him my name.

While all this was going on, the waitress just stood there looking down at us in amazement with her mouth open. Finally, I looked up and asked her if anything was wrong. She hesitated a second, then said, “Y’all mean to tell me that the two of you jus’ walk in heah an’ sit down an’ eat together — with conversation an’ all — an’ y’all don’ even know each other? That’s the funniest thing I ever heard of!” All three of us laughed at the absurdity of the situation; then Buzz told her how we happened to be together. “Well, anyway”, she said after he had finished the story, “y’all have a nice trip, an’ stop in an’ see us when y’all come back this way again, heah?” She walked away, shaking her head in disbelief.

As we pulled out onto the highway again, I said, “Well Buzz, if all goes well, our next stop will be your home, Midway. In a few minutes we’ll cross the Savannah River, and once past Savannah, it should be smooth sailing from then on”. He nodded in agreement, then looked at his watch. “It’s only a quarter after five now”, he said. “With a little luck I’ll be home before sundown”.

Now the highway was cutting a path as straight as an arrow through the marshland. The only vegetation to be seen was the tall wiry marshgrass on both sides of the road. It extended on either side as far as the eye could see. Looming up in the distance was the bridge over the Savannah River — the boundary between South Carolina and Georgia. The bridge is pitched so high above the river (and the surrounding terrain is so flat) that from a distance it seems to be taking off into infinity. When approaching it on a clear day, from the Carolina side, it can be seen from a distance of about seven miles!

As we got closer to the river, I became aware of a mixture of highly unpleasant odors. To my nose, they seemed to be concocted of potions of every foul-smelling chemical I had ever had the misfortune of being exposed to. The nearer we approached the river, the stronger the stench. Until, at the border of the river, it leveled off on a plateau just below the threshold of the limit of human endurance. A few hundred feet before the entrance to the bridge was a sign (obviously placed there at the behest of someone in the Georgia Tourist Bureau, endowed with a macabre sense of humor). It consisted of the face of a smiling sun with a legend encircling it, enticing us to: ‘STAY AND SEE GEORGIA!’ Just below this, some wag had tacked on a piece of white cardboard on which was written, in black paint, this message of caution: ‘AND DON’T FORGET TO BRING YOUR GAS MASK!’ Considering the assault my sense of smell was now suffering, I thought this addendum excellent advice.

Glancing at Buzz, I saw that he had his nose screwed up and his face wore a look of general discomfort. “Man, that’s some odor”, I said. “You damn right it is”, he shot back. “It smells like some of first one thing and then another”, he went on (using an expression that Southerners employ to describe highly unpleasant smells). “You know, every time I pass heah, it seems to git worse! Where’s it all goin’ to end?” “Well, anyway, welcome to Georgia”, I said.

Looking down from the center of the bridge, it was impossible to see the river’s surface. A thick haze of soot, smoke, chemical waste and miscellaneous discharges hung over it like a soggy blanket. I could barely see the outlines of tugboats on the river below and the industrial plants that lined the bank of the waterfront on the Georgia side. The full force of the stench rose up, slammed itself against my nostrils, reached down into my lungs and turned them inside out. Buzz started coughing, he took a handkerchief from his pocket and held it over his nose. I speeded up the car in order to get out of this poison as quickly as possible.

At the other end of the bridge, there were a series of toll booths. I wondered how in hell their occupants could stand this torture day after day without either jumping off the bridge or going mad. The attendant who took my money was extremely surly — I didn’t blame him, considering his working conditions!

Just off the bridge, there was a sign advising us to take ‘alternate route 17A’ in order to avoid going through Savannah. I decided to follow its advice. It took only a short time to discover that this route, like parts of its Cousin, I-95, had carved itself out of bits and pieces of streets that skirted the City of Savannah. It conducts a grand tour through parts of the worst slum south of Newark, New Jersey. The only other that can compare with it, in my view, is one on the west side of Jacksonville, Florida. By a strange coincidence, the inhabitants of both are black!

There were a great many people sitting on their front porches and, as we drove past, many of them waved. The surfaces of most of the streets were in such terrible condition, that any speed above five miles per hour would have been hazardous. In some cases, the streets ran so close to the buildings that it would be possible for someone sitting in a chair on a front porch to shake hands with someone sitting in a car on the street without getting up. Some buildings looked as if a strong gust of wind could dislodge them from their pillars. They were all frame buildings and most were one story high. I saw several whose walls were actually being supported by long poles propped up against them. Occasionally, there were inhabited dwellings that were constructed of tin sheets. To top it all off, every once in a while, we passed one of these derelicts that stood there empty — in all its grandeur — sporting a ‘for rent’ sign on its front wall!

Frequently, we passed a run-down shop or restaurant with little clusters of men gathered on its front porch. The older men looked just as the older men who gathered around these places had looked when I was a boy. For the most part, they were dressed in denim shirts and overalls with a smattering of khaki work pants thrown in. They were generally shod in that variety of work shoes that used to be known as ‘Brogans’ (the function of which is not to be confused with the current fashion trend among hippies, college students and city teenagers in general (theirs are for working). A sweat-stained felt hat usually capped off the uniform. The few who were bareheaded wore closely cropped hair. There were no signs of processed hair anywhere.

The teenagers and younger men were of a different breed entirely! Their dress styles ranged all the way from flamboyant purple shirts, tucked inside multi-colored pants (which in turn were hung over alligator skin shoes; through denim jackets with tight-fitting Levi’s, on to dashikis combined with chinos and sandals. Their hair styles, with few exceptions, was of the style known as ‘Afro’.

To the casual eye, these little knots of men might seem, at first glance, to be made up of widely disparate elements; yet they were bound together by two of the strongest links in the chain that unites all black Americans — sometimes involuntarily — color and economic condition.

There were many restaurants that catered to the palates of those whose tastes favored highly seasoned foods. In one block alone, I counted four such establishments, each of which displayed signs proclaiming its absolute supremacy in the culinary art of preparing barbeque! Once in a while, I saw one that advertised ‘soul food’, but not often. There was one which (in a display of supreme confidence) omitted any reference as to category of food served. It referred to itself, via a large neon sign, simply as the ‘Down Home’! Thus, assuming, I suppose, that the genre of its cuisine was common knowledge and therefore needed no additional publicity.

The hardy aromas of various types of barbeque sauces wafting out from these restaurants were in welcome contrast to the ‘essence de river’ that had just recently overwhelmed us.

Near the end of this section we stopped for a traffic light. While waiting for the ‘go’ signal, a black youth of about nineteen sauntered up to the curb and started to cross the street. As he came abreast of the car on my side, he suddenly darted out of the crosswalk and, poking his head inside the window to within two inches of Buzz’s face, he yelled in a voice dripping with venom: “Hiya, honky”. Almost in the same motion, he withdrew his head, went back to the crosswalk and continued walking toward the other side of the street as if nothing had happened.

Buzz sat there stunned! His face was as red as the heart of an overripe watermelon. It had happened so quickly that he had had no time to react. “Well I’ll be damned!” We both blurted almost simultaneously. Just then the light turned green and we drove on. For a time we rode in silence, each of us digesting in his own way the impact of that incident. I turned to him finally and said, half jokingly, “Well Buzz, there’s another on of those ‘new terms’ for you to mull over!” He laughed and the tension was broken.

By this time, we had left the slums and odors of Savannah some distance behind us. It was almost certain now that Buzz would get his wish to be home before dark. The sun was still about four o’clock high and Midway was only fifty miles away. When I commented on this fact to Buzz, he nodded absentmindedly. It was as though home was no longer of any concern to him. His mind was obviously somewhere else — back in Savannah.

“Why the hell y’all think he did that?” he asked. “The guy must be crazy! Did y’all ever see anythin’ like that in yo’ life?” I answered that once before, during World War II, I had witnessed a somewhat similar incident. “Yeah, what happened?” He wanted to know. “Well, we were on this troop train traveling through Mississippi when it happened…Our train had stopped to take on fuel and some of the fellows decided to take advantage of this and sent someone to a nearby store to buy some fruit. Just as the guy came out of the store, the train started to take off. Another soldier stuck his head out of a window and started yelling and waving to his buddy to hurry up before he was left behind! As the train was picking up speed, it passed a loading platform next to the tracks. A small white boy about ten years old who was standing on the platform near its edge, slapped the face of the soldier with his head outside as hard as he could and yelled: “Hey Nigger, git your goddamned head back inside!” Since the train was going in one direction, and the blow came from the opposite one, its effect was increased about five times! The soldier’s head slammed into the side of the train with such force that he lost two teeth as a result. I looked out of another window and saw the kid still standing there on the platform, laughing and shaking his fist in our direction. By the way, the other guy managed to get back on the train”.

Buzz looked at me in amazement. “Did anybody catch the kid?” he asked. “Are you kidding? In Mississippi? Not a chance! If anybody saw him, they probably gave him a medal for courage beyond the call of duty”. “Goddamn!” was all Buzz could say. “So you see”, I concluded, “You were lucky –you were only assaulted verbally!”

Buzz let that sink in for a moment, then said emphatically,

“Man, growin’ up down heah in yo’ time musta been hell!”

“It was”.

“Then why the hell you comin’ back?”

“I’ve asked myself that question at least a hundred times since I left New York. I suppose one reason is to see if things have changed much for the better. Another is to find out if it is possible to come to terms with my past. I guess that’s something most of us must try to do sooner or later, if we live long enough to create a past. Also, lately I’ve been thinking a lot about the old homestead and the family I left back here and I have a strong desire to see them both again”.

“Apart from these things, during the last five years, I’ve belatedly come to realize that, insofar as Blacks are concerned, the North is basically no better thatn the South — only different. So if I find things changed enough to make a readjustment possible, I might consider coming back home for good.”

Gettin’ a little tired of the rat race, eh? Buzz asked. “You bet!” I replied. I asked him what his plans were after he got home. He said he would go to work as a salesman in his father’s used-car agency. His family had been in business in Midway since shortly after the Civil War. His great grandfather had founded a farm-implement, seed and livestock business with only two mules and three headplows at the start. From this shaky beginning, the business prospered to such an extent that by the end of the first World War it was one of the largest of its kind in southeast Georgia. The Depression came and it all went down the drain!

Buzz’ father had started all over again. Going into the used car business during the second World War. Since new cars were hard to come by during this period, his timing could not have been better. By the end of the war, he had three thriving used-car dealerships in the area. One of the main reasons for Buzz’ leaving home was his father’s desire that he learn the business in preparation for one day taking over completely. Since he found the idea of becoming a used-car tycoon unappealing, and as there were no other local alternatives that suited his fancy, he’d just packed up and enlisted.

Now he was happy to be back. I asked if he thought it would be difficult for him to readjust to the pace of a small town after all the excitement of the past fifteen years. He answered my question with one of his own: “If y’all had the choice of facin’ some guy and tryin’ to talk him into buyin’ a used car, or facin’ some “Cong” in the jungle of “Nam”, what would you do?” I didn’t answer, the choice was obvious.

The highway suddenly expanded itself into two lanes. A large, ornate sign over it welcomed us to the town of Midway, Georgia first; then, threatened us with dire consequences should we be so rash as to violate any of its traffic laws. “Well Buzz”, I said, “You’re home. Where do you want me to drop you off?”

“When you come to the third traffic light, you’ll see a Gulf fillin’ station on yo’ right. It belongs to my Cousin. Pull in there and stop.”

“Okay,” I answered. As we pulled into the filling station, I looked at my watch. It was five minutes to seven.

As we got out of the car, a black attendant came over. When he saw Buzz, his face broke into a big smile of welcome. “Well, I’ll be damned, if it ain’t ol’ Buzz! What y’all doin’ back heah? I thought y’all been still up dere in the hospital!” Buzz told him that he had quit the army and was home for good. He introduced me, then asked if his Cousin was around. He was told that his Cousin had just gone home for supper. Buzz then explained how we happened to be traveling together. He asked the attendant to check my car, make any adjustments necessary, fill the gas tank, and charge it to him.

Then he suggested that I come home with him and meet his family. He said I could have dinner with them, spend the night at his house and finish my journey the next day. He said that he’d like his folks to meet me and assured me there would be no problem about my staying. I thanked him for the offer, but said that since I had only about seventy miles still to go, I wanted to get home that night.

After wishing me luck and warning me to be very careful while driving through the towns of McIntosh County because they extracted a large share of their revenue from the pockets of unwary out-of-state motorists, he asked if I had something to write on. I took a piece of paper out of the glove compartment and handed it to him. He wrote his address and phone number on it and handed it back. Then he said that anytime I was passing through, to feel free to stop by for a visit. I said that I might just do that. He told me that anyone at this filling station would give me directions to his home. I gave him my address in return, then said that I had better be on my way.

There was a moment of awkward silence as we stood there just looking at each other. Finally, Buzz stuck out his hand and said, “Y’all know somethin’, Bill? I sho’ enjoyed travelin’ an’ talkin’ with you. An’ I’m gon’ tell y’all somethin’ else — I like you, I like you a lot! An’ I sho’ hope y’all fin’ everythin’ alright when y’all get home. Now, y’all be careful on that road out there, you heah? Well, so long an’ may God bless an’ keep you!” I said goodby, got back in the car and started off on what I hoped was the last leg of my journey.

I had now been on the road for about twenty-four hours straight, and gradually I became aware of the beginning signs of fatigue creeping over me. It was now night and the greatly reduced visibility — coupled with the necessity for increased alertness introduced by this fact — added an extra strain, which heightened my sense of weariness. The thought crossed my mind that I might have been too hasty in rejecting Buzz’ offer to spend the night at his home.

For a moment I considered turning around and going back to Midway. But a quick glance at the odometer disabused me of that notion. I had already covered twenty-two miles since leaving there. The distance back was about the same as that to the next town ahead. I decided to continue on as far as Brunswick, Georgia which was only about thirty miles distant, and stop there for the night if I felt too tired at that point to proceed. This would leave only twenty-eight miles to cover the next day before reaching home.

Before picking up Buzz I had made occasional stops in roadside rest areas to wash up and take short rests. I usually spent about fifteen minutes walking around and doing about five minutes of calisthenics to increase the circulation and loosen up a bit before continuing on my way. In addition, I made infrequent stops to photograph people or things I found interesting. This routine, plus my desire to see everything of interest along my route that could be observed without jeopardizing my own safety, or that of others, had helped to keep me alert. After taking on my passenger, except for food and fuel, I had made only four brief stops to take photographs, and none for exercise. Our conversations and my interest in the surrounding terrain had been sufficient to keep me pepped up.

None of these options were available to me now. Even reading the neon signs that were strewn on either side of the highway like multi-colored electric hookers enticing me to try everything from Bibles to boathouses (at a price, of course), put an added strain on my eyes. Therefore, I kept my eyes off them as much as possible. This was no easy task, for they stood out in bold relief against the surrounding darkness and it was almost as difficult not to look at them as it is for a moth to ignore the fatal attraction of a lighted lamp.

I decided to hold my speed down to thirty-five miles per hour, even though the limit posted advised me that I had the choice of living dangerously and doing fifty, if it suited my fancy (and stupidity). I was now traveling on home ground. Even in the darkness I could occasionally recognize the outlines of some landmark that I remembered from years ago. There were more built-up areas along the borders of the highway, but there were still long stretches of countryside in between. Except, of course, for those ubiquitous neon hookers. They seemed to have been spaced with extremely diabolical cunning. Sometimes they would fake me out by giving me up to a twenty minute respite — no signs at all! And then, upon rounding a curve or coming out of a thick grove of trees — Wham; they let me have it, literally, in the eyes!

Judging from many of these neon (and other types) signs, it would seem that the major competition for the highway traveler’s dollar (at least insofar as food, fuel, lodging and certain regional products are concerned) in the southeastern coastal states, is among three firms: “Stuckey’s”, “Horne”, and “Rawls’”. With Mr. Rawls occupying, I believe, a tertiary position. The first two usually supply food and lodging, in addition to their other services; the third may or may not.

From the time I passed Washington, D.C., signs bearing the imprint of the establishments listed above repeatedly urged me to purchase samples of almost every variety of agricultural product grown in the southeast. In Virginia, they touted ham and tobacco; in the Carolinas, the pitch was cigarettes, ham and pecans; and in Georgia, they were hustling peanuts, pecans, peaches, ham and (in the southeastern section) citrus by-products. There were, of course, other firms competing for these markets; but the names of “Stuckey”, “Horne”, and “Rawls” led those of the other entrepreneurs of the open road by a wide margin!

In several instances, I saw two of the three facing each other from opposite sides of the highway, like two gunslingers preparing for a showdown – winner take all! In Virginia and North Carolina, Stuckey and Horne had the market pretty much to themselves, but, somewhere in upper South Carolina, Mr. Rawls put in his appearance, and by the time I reached the Georgia border, he was engaged in a ferocious war for outlet location and highway advertising space with the other two.

Of all the products I saw touted along the way, there was only one that seemed to enjoy equal popularity (judging by the amount of advertising) in every southeastern state. It seems that the residents of these states are under the impression that they suffer from a dearth of ear-shattering noises. In a heroic effort to cope with this deficiency, many roadside entrepreneurs, from Virginia to Florida, give a product known as “fireworks” prominent display, both among the wares in their emporiums and on their advertising signs. There are also many firms that specialize in the sale of fireworks alone. Relatively few of the establishments I saw on the trip, or the garish signs that touted them (as well as those touting various other items) were in existence when I went away.

Coping with the distractions of this surfeit of signs had presented no problem for me during the day when I had been much fresher, and the current for the majority of them was turned off. Now, however, it was a different story! I was tired and tense and the sight of all those colorful lights beckoning me made my eyeballs want to burst. The small amount of extra illumination they cast on the highway was more than offset by their negative effect upon my psyche. I finally resorted to the tactic of blinking my eyes rapidly for a few seconds periodically in an effort to erase their images from my brains. This solved the problem and for the rest of my journey I was not too conscious of them.

All at once, as if it came out of nowhere, I saw a sign announcing the city limits of Brunswick. For a moment, I thought my eyes, in their fatigue, had played a trick on me. Then I saw another larger, neon-lit sign that removed all doubt. Written on it was the legend: “Welcome to Brunswick, Gateway To The Golden Isles”. That confirmed it. I was now only twenty-eight miles from home!

I had assumed that I was still somewhere north of Darien, some thirty-five miles north of Brunswick. But I had been so absorbed in trying to cope with those damn neon signs, that I had gone right through Darien without being aware of it. Glancing at my watch, I saw that it was only nine-thirty. As I was feeling only a little more fatigued than when I left Midway, I decided to put caution to the winds and try for home.

Within a short while, I was cutting through the marshes of Glynn, the subject of Sidney Lanier’s epic poem of the same name. My fatigue had miraculously disappeared, and I felt almost as fresh as when I started out. Shortly, I saw a sign announcing the Little Satilla River, and right next to it, another that marked the beginning of Camden County. Soon I was whizzing through little villages and hamlets, the names of which had not crossed my mind in years: Spring Bluff, Waverly, White Oak. So far as I could tell in the darkness, they seemed not to have changed one iota in all the years of my absence.

Five minutes after leaving the hamlet of White Oak. I could see the well-lit bridge over the Big Satilla River. As I got closer, I could see that at least one thing in Camden had changed in my absence: the old bridge I had known had been replaced by a more modern one of reinforced concrete. Once on it, I saw that it arched over the river at a much higher distance above the water than the old one had. At its opposite end was a sign announcing that the city of Woodbine, Georgia began there. Another dramatic change was immediately apparent. In place of the one lane thoroughfare of my youth, there were now two lanes in each direction that ran almost up to the foot of the bridge. A short distance from the bridge was a traffic light. Beyond that, I could see three more lights in the distance!

“Well I’ll be damned if Woodbine hasn’t gone modern!” I said out loud in stunned surprise. It was now three minutes past ten. The trip from New York had taken me exactly twenty-two hours. The odometer showed that I had covered a distance of one thousand twenty-three miles!

I knew that just a hundred feet or so from the bridge, there should be a dirt road on the side of the highway that would take me the three and a half miles out to my old community – Scarlet. It wasn’t there! I pulled off the road, stopped, and got out of the car to get my bearings. That road must be around here somewhere, I thought to myself. I haven’t been away long enough to forget where that road was. I stood there a few moments trying to recreate the town as I remembered it in my mind’s eye. As the path slowly came into focus, I looked at the buildings around me trying to match them with those I saw in my mind. No luck; they wouldn’t fit! Finally, I walked the short distance back to the bridge, then retraced my steps back to the car, carefully examining each building as I went along. I saw only one building I recognized – Gowen’s Appliance Store. It had been erected just before I left home and was the most modern building in the town at the time. None of the other buildings were familiar.

I got back into the car and just sat there for awhile trying to decide what to do next. The town had rolled up the sidewalks for the night and there was not a single person to be seen anywhere. The few residences adjacent to the highway had their shades drawn and (so far as I could determine) their lights out. I finally decided to continue a bit further along the highway in the hope of finding a filling station or an all-night truck-stop open. Besides, the prospect of being spotted by some trigger-happy small-town Southern cop, who might consider the coincidence of a strange black man sitting alone in a car with New York plates parked in the commercial part of town at this hour, reason enough to shoot first and ask questions later, was certainly unappealing.

After traveling about a mile further, I came upon an ice plant with a store and filling station adjoining it. A sign over it said it was open twenty-four hours. With a sigh of relief, I pulled off the highway and stopped in front of the store. I went in and asked the woman behind the counter if she could direct me to Scarlet. She replied that she was new in town and had never heard of it. As I turned to leave, she said that I might try the colored night man working in the ice plant next door, as she believed he was a native of these parts and lived about three miles from town, “somewhere out on route 110.” I thanked her and headed for the ice plant.

As I walked up the steps to the loading platform, a black man of about fifty-three years of age came walking out of one of the freezing stalls pulling a large block of ice behind him. After apologizing for the intrusion, I asked if he could direct me home, and also if he knew my Uncle, Aaron Weston. His reply was, “Yeah, not only do I know your Uncle Aaron, but I know you too!” He turned out to be one of my distant Cousins, James Forcine, who I had grown up with. He had recognized me on sight; but my memory was not as acute. It was only after talking with him for a few minutes and studying his facial features, was I able to reconstruct his image as I had known it.

After exchanging the customary amenities, I told him about my embarrassment at not being able to find the road home. He laughed at this, then told me there was no need for embarrassment on my part, for not only had the road been moved since I went away, its surface had also been paved. It was now rated as a “Class A” highway and was known as “State Route 110”. He added that at the same time the road was paved, parts of it were straightened out and that its junction with U.S.17 was about a block further south than previously.

Next, he informed me that Uncle Aaron had just recently passed by on his way back home after taking his wife to the hospital and leaving her there. I asked what was wrong with my Aunt. He replied that she was a diabetic and had to be placed in the hospital periodically for observations and check-ups. I asked if there was any place in town where I might get some food, as I was hungry. He replied that he didn’t think so.

He looked at me for a moment in silence, then asked: “Junior, when last you ate anythin?”

“About five o’clock this afternoon, in Hardeeville, South Carolina” I answered.

He looked surprised. “You mean to say you drove all the way heah from there since five o’clock?”

“Yeah. I’ve been on the road since last midnight.”

“Without stopping to sleep or anythin’? Man, you musta been outa your mind!”

“Well, you see, when I started out, my intention was to make the trip in about three days, but once on the road, I got a strong desire to get home so I just kept on going and here I am.”

“Well, I’ll be damned! Boy, you done come over a thousand’ miles!” “You come by yourself?”

“Most of the way. I picked up a white soldier in Summerton, South Carolina, and he rode with me as far as Midway.”

“How long since you been home?”

“About thirty years or so.”

“Thirty years! Damn! How old are you now?”

I told him I was “Forty-nine.”

“I’m fifty-two and a grandfather! Well, Junior, I guess we gettin’ kinda old, ain’t we?”

“Yeah, I guess we are.”

“You got any children?”

“Yeah, two – a daughter of twenty-five and a six year old son. No grandchildren yet; my daughter is not married, and my son is too young.” We laughed.

Then, I asked about some of the older people I had known in my youth. His answer: “Junior, a whole lot of them old people done gone from heah! Mama and Papa, they both dead. There’s still some of the old folks around, though. Your GrandUncle Sonny, he still heah, he about ninety-four years old now. An my Uncle Cleveland, he still heah — doin’ fine at eighty-five, an’ still chasin’ women! Then, there’s Mrs. Katy Jones — she must be eighty-some; old man Derry Toney — he pushin’ ninety; old lady Sarah Jenkins over in St. Mary’s — she about ninety-three or ninety four; anyway, she aroun’ Uncle Sonny’s age. An’ there’s a few more knocking about out in these woods somewhere, whose names I can’t remember just now. Come to think of it there’s quite a few old folks aroun’ heah — still hangin’ on somehow.”

He paused a minute, then said: “Boy, I never expected to ever see you down this way again — after we didn’t hear from you in so long. Mos’ o’ them that left from aroun’ heah come back to visit from time to time; but now you, you ain’t come back to visit even once ’til now. What made you decide to come home after all these years?” “There’s really no simple answer to that question”, I replied. “Let’s just say, as the old folk used to, that there’s a time for all things, and this was the time for me to come back home.”

“By the way”, I asked, “have you been living here all these years?”

“Yeah, ever since I come home from the C.C.C. camp. You know, I met my wife, Pearl, when I was in the corps up there in Jasper, Georgia. Brought her back home and we been heah ever since. I been workin’ heah at the ice plant twenty years — ever since they built it. Yessir, seven nights a week for twenty years — except for two weeks vacation each year! I got me a driller’s rig an’ run a well-boring business on the side. I also do the meter readin’s for the town of Woodbine.”

“When the hell do you sleep?” I asked.

“Oh, I manage to get in a few licks here and there”, he answered. “I’m the only one here at night and I set my own pace”, he went on. There ain’t nobody aroun’ to bother me — I’m my own boss! It ain’t too bad at all”, he concluded.

“Well, James”, I said, “it’s a little after eleven o’clock, so if you will be kind enough to tell me how to find the road home, I’ll be on my way. I expect to be here for at least ten days, so I’ll stop by your place before I leave. “You know”, I added laughing, “if anyone had told me that I would ever need instructions on how to find Scarlet, I’d have called him crazy!”

He gave me explicit instructions on how to find the road and we shook hands. As I turned to leave, he said, “Wait a minute! I forgot all about you bein’ hungry. I’ll phone Pearl and tell her you comin’, an’ to fix you somethin’ to eat. You can’t miss our house; it’s at the crossroad, where the artesian well used to be.”

“You’ll what?”, I stood with my mouth open.

“I said I’ll phone her.”

“You mean to say you have phones out there in the woods now?” “Yessir, an’ gas an’ electricity too. We got just about everythin’ out there you got in New York! It ain’t like in the old days when you was heah; that’s all changed now.”

James said goodnight and went back inside to call his wife. I drove slowly back down the highway until I saw the sign pointing to State Route 110. I turned onto it with a sigh of relief and headed for home, three and a half miles away. As I reached the city limits of Woodbine, I saw a sign carrying the legend: ‘POSTED SPEED – 60 MPH DURING DAYLIGHT HOURS; 50 MPH AT NIGHT, SPEED CHECKED BY RADAR’. Well, I thought, it seems that modern technology has finally caught up with the backwoods!

I drove slowly, looking on both sides for some familiar landmarks. I didn’t see any. That didn’t upset me unduly, as I knew that the road passed through a swamp that had hickory groves on both sides and seven small wooden bridges within its confines. About a quarter of a mile beyond this, was the crossroad, and home! I kept a sharp eye on the lookout for those hickory groves and that swamp; but to no avail. Presently, I came upon a crossroad. This can’t be the one; I got here too quickly, I mused. But just to be sure, I turned into it and pointed the headlights toward the place where I remembered the community’s mail boxes used to be located — about twenty in all, lined up in a row, on one long shelf. Nothing! Having thus satisfied myself that this must be a new dirt road, built during my absence, I backed the car out on the main road and continued on my way. The few houses that I could make out were all dark and quiet, with only the occasional barking of a dog as I passed, to break the stillness. I was still looking for that swamp and crossroad without success. Then, I suddenly remembered another landmark — and this one I was sure would still be there — the community cemetery! It should be on my left, about half a mile before I reached the swamp; but I didn’t see it either.

Just as I was considering turning back, I saw a sign with the “T” symbol for ‘dead end’, and the stem was facing me. Beneath this, another sign said that Junction 40 was just ahead. A few minutes later, route 110 came to an end as an entity, and merged with the new road. At their intersection, a group of directions were posted. One of them stated that the town of Folkston, Georgia was only eight miles distant. Involuntarily, I slammed on the brakes and sat there in frustrated embarrassment. Unless the town of Folkston had been picked up and moved closer to Scarlet, I had gone twelve miles beyond my destination! In other words, I was lost, again!

I began inwardly cussing myself for my stupidity. Now I realized that I could have avoided this predicament simply by having checked the mileage registered on the odometer when I entered route 110, and then, stopping when it had clocked approximately three and a half additional miles. But I had been so sure of myself at that point, that the idea never entered my mind. As a result of this oversight, I was now sitting in the middle of an area I had known as well as my name, completely disoriented for the second time within three hours!

I turned the car around and started back. By this time, every bone in my body ached; and my head felt as though it wanted to separate itself from my neck. I decided to stop at the first house I saw and bang on the door until someone opened it — even at the risk of being fired upon by some frightened householder. I was that tired. I kept the car moving by sheer force of will and silently thanked heaven that there were no other vehicles on the road at this hour besides mine. I maintained just enough speed to keep the car from stalling. A ten-year-old could have walked faster, without breathing too hard!

After about five minutes at this snail’s pace, I saw a light in the distance. As I came nearer, I saw that it was coming from what I took to be the back part of a house on the right side of the road. I pulled into the driveway, stopped and got out of the car, leaving the motor running and the headlights on. As I walked toward what I could now see was a screened-in front porch, I heard the sound of voices that seemed to be coming from the back part of the house. I knocked on the screen door as hard as I could. Almost immediately, a woman’s voice came from somewhere inside. It was unmistakably black!

“Who that out there this time o’ night?”, the voice queried. “Excuse me ma’am, but I’m lost and I wonder if you might help me”, I answered.

“Who you lookin’ for?”, the voice sounded closer.

“I’m looking for my Uncle, Aaron Weston; I used to live here myself, many years ago.”

“Who you?”, the voice asked.

Now I could see her silhouette behind the glass in the front door. “My name is William Mackey; but they used to call me Junior around here.”

“Not Junior Mackey?” she cried, opening the front door at the same time.

“I’m afraid so — and a tired and hungry one at that!”

In one bound she was at the screen door unfastening it. “Boy, come on in heah, I’m Lonnie Mae, you remember me. What you doin’ sneakin’ up on us in the middle o’ the night like this for? You like to scared me to death with the loud knockin’ out there. Come on in heah an’ let me look at you! My, my, ain’t you something! That’s jus’ like you, Junior — sneakin’ up on folks without tellin’ ’em nothin’! You always did have the devil in you. You ain’t changed a bit; come on in heah an’ sit down.”

At last I was home – finally! It had taken me twenty-two hours to drive the thousand miles from New York to Woodbine; then taken me three hours to cover the last three and a half miles from Woodbine to Scarlet!

I followed Lonnie Mae back to the kitchen and sat down at the table. For the first time since entering the house, I had the opportunity to get a good look at her as she stood there staring down at me and shaking her head in disbelief. I saw before me a pretty woman of medium-brown skin, rather short and on the plump side (but not unattractively so). Her hair, which was pinned up in the back, was greying ever so slightly. She had the face of a woman of thirty, but I knew that she had to be much older than that. I tried to picture her in my mind as she had been when I last saw her, but the image didn’t come immediately into focus. However, as we talked, gradually, the curtain of time lifted and I began to remember what she looked like as a girl. The last time I’d seen her, she was about fourteen. As if divining my thoughts, she said, “Junior, its been a long time, ain’t it?” “Yes, it sure has”, I answered.

There was a boy of about three playing with a toy train on the floor in the dining room. I asked if he was her son. She laughed, then said that he was one of their grandchildren, of whom there were several. She said they seemed to spend almost as much time with her as with their parents. She was a seamstress and was just now in the process of finishing a dress for a customer who needed it the next day; that was why she was up so late. She had been trying to get her grandson to go back to bed when I came up, and having no luck (as he had a different idea in mind). It was this conversation that I had head on arriving.

She asked when had I left New York and when I told her, she said that I must be out of my mind to do what I had done. I agreed, but added that was behind me now and, at the moment, all I felt was tired and hungry. She suggested that I take a bath while she prepared me some food. Adding that there was no need to open my luggage for clean underwear, as her husband was about my size and I could use a pair of his. I thanked her, then suddenly remembered that I had forgotten to turn off the motor and headlights of the car and I went outside to attend to it.

When I returned, the water was drawn for my bath and clean underwear was laid out on a chair by the bathtub. When I came out, some twenty minutes later, I discovered that she had awakened her husband and had him go out to the hen house and kill a chicken that she was in the process of cleaning in preparation for cooking. The table was already set and there was a glass of milk and a platter of cookies nearby for me to munch on while waiting for the chicken.

Her husband introduced himself as Laurie Drummond, Jr. I remembered the name as belonging to a local family, but did not recognize him. He also had been quite young when last I saw him.

After I finished eating, Lonnie Mae suggested that I call my Uncle to let him know I was home. She gave the number from memory, then, instructed me on how to dial it.

In a few seconds I heard my Uncle’s voice. It sounded just as it did when I last heard it. When I told him who I was he was flabbergasted. Briefly, I outlined the circumstances of my coming home, then told him I would be there in a short while. He said he would leave the light burning on the front porch so that I would recognize his house, which was only a short distance away.

After hanging up, I sat back down, shaking my head. “What’s the matter?”, asked Laurie. “Man”, I said, “I’m having one hell of a time adjusting to the changes around here! When I left this place, finding a lantern to light your way on a dark night could be a problem; now I come back to wall-to-wall television. It never occurred to me when I was at that service station in Woodbine that I could have looked in a directory, found Uncle Aaron’s number, and then dialed! Even after James Forcine told me that he had a phone, I didn’t make the obvious connection! Hell, sitting here in your kitchen is no different from sitting in mine back in Brooklyn. You’ve got a washing machine, refrigerator, freezer — the works! I guess you might say I’m suffering from a mild case of culture shock!”