A letter from my Aunt Rachel Jullum in Norway, to my Grandmother Tordis Jullum Bornholdt in the United States after World War II

Translated from the original Norwegian

Tonsberg, Norway

1945

Dear Tordis,

At last, I can write to you again after these awful years. You have no idea of how things have been and what a relief it is that it’s over, and over in such an incredibly simple way. The first week of peace was so beautiful that it is hard to describe. We weren’t still a minute, we walked around the streets and just enjoyed seeing nothing but happy faces. We laughed and cried each time we saw a child with a flag and as all the children walked around with flags all day, maybe you can imagine what a strain that was.

Then we ran around to the lucky people who had had their radios returned (very few). Their living rooms were chuck full of strangers who came in to listen to Churchill, the arrival of the Crown Prince at the airport, etc. Each day something new and wonderful and thrilling happened. In Oslo, there was dancing every night on the street corners and bonfires mand from blackout curtains.

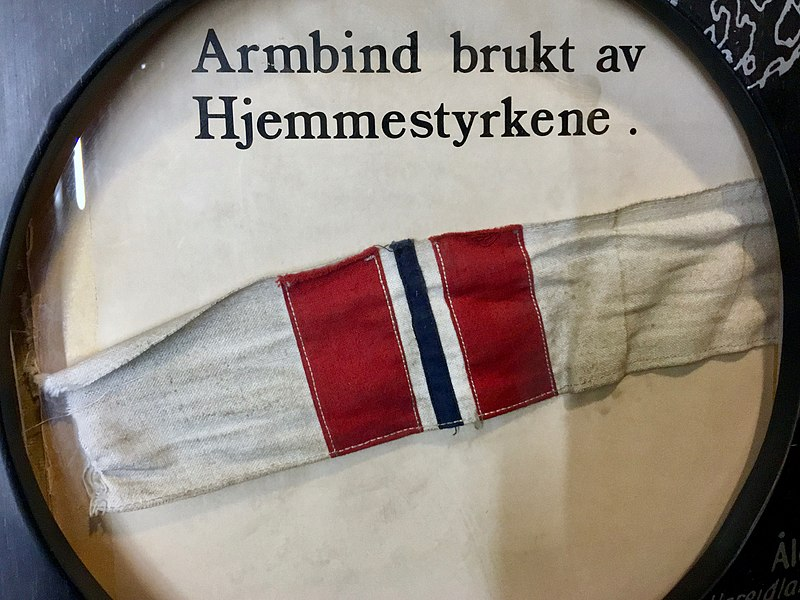

Then the prisoners from Grini (the largest concentration camp in Norway just outside Oslo) came, then Seip (Pres. of the Univ. of Oslo) and all those who had been held in Germany arrived. They came from Sweden and from England, all those who had been away all these years. The whole thing was unbelievable. Then all the boys in the “homefront” (underground) came flooding into the city. It was amazing to see how many there were, all in ski sweaters and knickers, each one different, so touching and such a relief after all the German uniformity.

I had been mobilized for the home front in case of military operations, which we were sure were coming, but I had never dreamed that everything would be as marvelously well organized as it turned out to be. Fortunately, they didn’t need us, so my little contribution after peace was to make sandwiches for the home forces from three in the morning until nine at night every other day. The food was from Denmark. It had been smuggled here to keep all the boys alive who were living in the woods and in the mountains and who were training right behind the backs of the Germans. The Danes have been wonderful. They sent food to the families of the prisoners and of seamen. It all had to be smuggled in, for everything was against the “law” and those who distributed it were constantly sought by the Gestapo.

During these years I wrote you a diary of all the things that happened to us, strange things, sad and tragicomic – all mixed up together. I wanted to write them down while I remembered them and I knew that when peace came I wouldn’t have the time. But I am sorry to say that after two raids by Gestapo and one by local quislings I didn’t dare keep it. It would have landed the whole family in Grini, and that was after all rather a high price to pay. It was with real regret that I watched it go up in flames.

I was very lucky the first time they were here. I was only kept for twenty-four hours in Berg concentration camp, and they let me go with only the penalty of reporting every day. They found a list of the prisoners at the Berg concentration camp in my apartment, and a list like that has landed many a person in jail for months. The men who took me were not too bad. They threatened me with all sorts of horrible things, but gave up and let me go although my explanations were anything but satisfactory and seemed to exasperate them. One of my girlfriends who was arrested at the same time was not so lucky. They took her to Gestapo headquarters in Larvik. There they took a stranglehold of her and beat her face with their fists, threw her on the floor, and kicked her so hard that her ankles are still swollen. They knocked out a tooth and when she asked them what the idea of that was, they comforted her with “Sie brauchen keine Zahne” (you won’t be needing any teeth). You understand that it was a “Herrenvolk“we had here and if you have heard tales of torture and other terror, be sure that they are not exaggerated. We have seen so much that is brutal, often ugly, and comical at the same time, that if we had not been so stubbornly optimistic and naive in our firm faith that it all would come out all right in the end, we never could have stood it.

We were very efficiently organized with regard to illegal newspapers and news. So many amazingly intelligent people have worked underground that it all seems a miracle. Everybody distributed newspapers, old people like our Tante Karen, housewives with children who really had all they could do to scrape together food for the family, young boys and girls. Some lucky ones also managed to get hold of Swedish books and you may be sure we devoured them. They were literally read to shreds. The mental terror was the worst feature of it all, the lies and the indignities continually flung at us.

We never starved, but of course, there were many who had too little, and there was much we never would have eaten in normal times. We had half-rotten fish about every other day the whole time. Swedish and Danish soup kitchens must have kept many people alive. But people in the country had enough. And, as you know, we are a people of farmers so many people didn’t suffer at all. But clothes and shoes are something else again. People are surprised at how well dressed we are compared with people in other occupied countries. If this is so, it’s only due to our resourcefulness. Good gracious how we have mended and patched and turned clothes inside out and dyed them. My summer coat is my one winter dress. My one summer dress is the lining of a pair of drapes, dyed. However, I won’t complain. It’s a thousand times worse for those who were children when the war broke out and who now need adult clothes. It is impossible to make overshoes. Our footgear is wood, paper, and fish skin.

I was planning to come to the U.S. in 1939 to do some graduate work. I often regretted that I didn’t go because it seemed to me that I could do so little here to help. But now I’m glad I stayed. We have gotten along quite well, even Bjarne (cousin) who, as you know was in Grini for four years. Mother has nearly worked herself to death helping the poor people who were evacuated from Finmarken. They were dirty, sick, and covered with vermin, but so calm and controlled. Sometimes they came through 1,700 a day. That is a tragic chapter. Agnes (sister) has been in Floro the entire time. She was dying to go to Svolvaer to join the English when they were on their famous raid, but she had a large class of boys and girls just getting ready for finals, and didn’t have the heart to let them down. Aslaug (another sister), was up to many mysterious things during the occupation[i], but was lucky and didn’t get caught. Hurry up and write.

Love,

Rachel

For a look at what Rachel was doing a mere 5 years later, see this post:

A Woman Dentist? Who’da Thunk it?

[i] Rachel’s sister, my great Aunt Aslaug was a very active member of the “homefront” resistance. Rachel is referring to Aslaug’s adventures in the Norwegian underground for which she received a medal after the war.