Contents

The Definition of The Word Barbecue

The Primary Clarification

The Secondary Clarification

History of Barbecue

The Native Americans & The Spaniards

Regional Traditions

The Southeast

The Carolinas

Memphis

Kansas City

Texas

The Magic & Science of Barbecue

Why not grill?

Why Barbecue?

The Magic Number

MORE INFORMATION

The Definition of The Word Barbecue

The dictionary will tell you that the noun “barbecue” has at least four meanings:

- A framework to hold meat over a fire for cooking

- Any meat broiled or roasted on such a framework

- An entertainment, usually outdoor, at which such meat is prepared and eaten.

- A restaurant that makes a specialty of such meat.

The United States Department of Agriculture says barbecue is:

- Any meat “cooked by the direct action of heat resulting from the burning of hardwood or the hot coals for a sufficient period to assume the usual characteristics” including the formation of a brown crust and a weight loss of at least thirty percent.

There are many interpretations of the term ‘barbecue’ in the world. Some people use it to describe a social gathering and cooking outdoors. Others use it to describe grilling food.

For our purposes here, we will use the following definition:

- Meat, slow-cooked, using wood smoke to add flavor.

The Primary Clarification

Barbecuing is not grilling.

Grilling is cooking over direct heat, usually a hot fire for a short time. Barbecuing is cooking by using indirect heat or low-level direct radiant heat at lower temperatures and longer cooking times. The distinction between barbecuing and grilling is the heat level and the intensity of the radiant heat. It is the smoke from the burning wood that gives barbecue its unique and delicious flavor.

Conversely, Grilling is not Barbecuing

The Secondary Clarification

Hot vs. Cold Smoking.

There are two types of smoking, cold and hot:

- Cold smoking is a method of preserving meat. First the meat or fish is soaked in a brine solution, then smoked cold at temperatures of 100F or so. Bacon is done this way.

- Hot smoking is really barbecuing (also known as “smoke cooking”). It is done at temperatures in the 195-275F range and will not add any preservation to the foods.

History of Barbecue

The Native Americans & The Spaniards

When the Spanish arrived in the Americas, they found the Taino Indians of the West Indies cooking meat and fish over a pit of coals on a framework of green wooden sticks. The Taino word in one form barabicoa, indicated that wooden grill and in another, barabicu, a “sacred fire pit.”

The Spanish came up with one word overall which referred to the grill, the firepit and the food that came from it: “barbacoa”. Both the name and method of cooking found their way to North America, where even George Washington noted in his diary of 1769 that he “went up to Alexandria to a ‘barbicue’.”

Regional Traditions

The contemporary barbecue traditions of most areas of are directly related to the cultures involved and the supplies were available at the time the area was settled by Europeans.

- When the Europeans first came to the east coast of the US, tomatoes were considered poisonous. The sauce of the day was vinegar-based, and the meat was cooked with local trees.

- The Caribbean has hot peppers, pimento trees, allspice, citrus, seafood, and hence jerk.

- The Kansas City area had grain for hogs, tomatoes were okay to eat, sugar from the south, and cattle and peppers came up from Texas. So we have an area that cooks beef and pork with a sweet tomato-based sauce with chilies.

- Texas had beef, peppers, post oak trees and mesquite; hence brisket with a chile-based rub, served dry is the regional favorite.

- The Northwest had game, plenty of seafood and alder trees; so Smoked Salmon became a standard there.

While there are numerous regions and sub-regions, for this discussion we will stick with the Southeast and Texas as these are the regions that are most often associated with “Real Barbecue” by the hardcore enthusiasts.

The Southeast

In the Southern United States, barbecue initially revolved around the cooking of pork.

It is generally believed that the Spanish explorer Hernando De Soto introduced hogs to Florida and Alabama in 1539. The settlers at Jamestown brought swine with them in 1607 and legend has it that soon thereafter Virginia enacted a law making it illegal to discharge a firearm at a barbecue! The creatures thrived in the wilds of the warm Southern woodlands where cattle perished. By the time of the Civil War, hogs had been domesticated, and pork had become the principal meat of the South.

According to estimates, prior to the American Civil War Southerners ate around five pounds of pork for every one pound of beef they consumed.

During the 19th century, pigs were a low-maintenance food source that could be released to forage for themselves in forests and woodlands. When food or meat supplies were low, these semi-wild pigs could then be caught and eaten.

Because of the effort to capture and cook these wild hogs, “pig slaughtering became a time for celebration, and the neighborhood would be invited to share in the largesse. The traditional Southern barbecue grew out of these gatherings.”

Indeed, barbecues have long been a popular social occasion in the South. But, done in the traditional way, the making of barbecue was hard work. A pit was dug in the ground the day before the gathering and filled with hardwood. The wood was burned down to coals before whole hogs, skewered on poles, were hung over the pit. The pitmasters sat up through the night, turning the hogs on their spits. The following afternoon when the guests arrived, the crisp skin – Mr. Brown – was removed and the cooked meat – the divine Miss White – was pulled in lumps from the carcass before being slathered with a favorite finishing sauce. That’s why, to this very day, a social affair centered around pork barbecue is affectionately called a Pig Pickin’.

In the Southeast, while the meat cooked may be primarily pork, and the method of cooking is fairly consistent, the major things that differentiate the sub-regional barbecue styles is the type of sauce served. Vinegar, red pepper, tomato, mustard, even mayonnaise are all ingredients which distinguish the regional barbecue styles within the southeast states.

The Carolinas

North Carolina sauces vary by region, Eastern North Carolina uses a vinegar-based sauce, the center of the state (around Lexington, NC) uses a combination of ketchup and vinegar as their base, and Western North Carolina uses a heavier ketchup base.

South Carolina is the only state that includes all four recognized barbecue sauces, including mustard-based, vinegar-based, light and heavy tomato-based.

Memphis

Barbecue is best-known for tomato and vinegar-based sauces.

Kansas City

From Memphis, Barbecue worked its way the 500 miles to the northwest to Kansas City. Here they added spice and molasses to the tomato-vinegar sauce of Memphis and created their own style.

Texas

In much of the world outside of the American South, barbecue has a close association with Texas. Texas barbecue is often assumed to be primarily beef. While this assumption is an oversimplification, when “Texas Barbecue” is mentioned, most of the time it means BEEF.

In reality, Texas has four main regional styles of barbecue, all with different flavors, different cooking methods, different ingredients, and different cultural origins.

- EAST – East Texas barbecue is an extension of traditional southern barbecue, similar to that found in Tennessee and Arkansas. It is primarily pork-based, with cuts such as pork shoulder and pork ribs, indirectly slow smoked over primarily hickory wood. The sauce is tomato-based, sweet, and thick. This is also the most common urban barbecue in Texas, spread by African-Americans when they settled in big cities like Houston and Dallas.

- CENTRAL – Central Texas was settled by German and Czech settlers in the mid 1800s, and they brought with them European-style meat markets, which would smoke leftover cuts of pork and beef, often with high heat, using primarily native oak and pecan. The European settlers did not think of this meat as barbecue, but the Anglo farm workers who bought it started calling it such, and the name stuck. Traditionally this barbecue is served without sauce, and with no sides other than saltine crackers, pickles, and onions. This style is found in the Barbecue Belt southeast of Austin, with Lockhart as its capital.

- BARBACOA – he border between the South Texas Plains and Northern Mexico has always been blurry, and this area of Texas, as well as its barbecue style, is primarily influenced by Mexican tastes. The area was the birthplace of the Texas ranching tradition, and the Mexican farmhands were often partially paid for their work in less desirable cuts of meat, such as the diaphragm, from which fajitas are made, and the cow’s head. It is the cow’s head which defines South Texas barbecue, called barbacoa. They would wrap the head in wet maguey leaves and bury it in a pit with hot coals for several hours, and then pull off the meat for barbacoa tacos. The tongue is also used to make lengua tacos. Today, barbacoa is mostly cooked in an oven in a bain-marie.

- COWBOY – The last style of Texas Barbecue also originated from Texas ranching traditions, but was developed in the western third of the state by Anglo ranchers. This style of “Cowboy” barbecue, cooked over an open pit using direct heat from mesquite, is the style most closely associated with Texas barbecue in popular imagination. The meat is primarily beef, shoulder clods and brisket being favorite cuts, but mutton and goat are also often found in this barbecue style.

The Magic & Science of Barbecue

So, just exactly what happens when you are cooking barbecue?

And why, for example, would we barbecue a beef brisket instead of cutting it into steaks and grilling it?

Well, to me, the answer is a little bit magic and a little bit Science.

First off, it is important to understand some science. Meat is made up of mostly protein muscle fibers held together with collagen strands along with a little bit of fat. Collagen is a particular type of protein that is very elastic. Collagen is also actually flavorless until it is denatured into amino acids. When the Collagen in a cut of meat is denatured by cooking, it has two effects: 1) Removing the elasticity, thus making the meat more tender. 2) Adding flavor to the meat.

Why not grill?

Because of the elastic nature of collagen, it takes more energy to denature it than other types of protein. When cooking, this means more heat is needed overall, HOWEVER, if the temperature is too high, the water in the muscle cells and the fat is rendered out before the collagen melts.

If you threw a slice of brisket on a grill, the high heat would cause the muscle proteins to contract, curl, and squeeze out the natural juices mixed with the liquefied collagen and fat. This would result in a piece of dry, tough meat. So, to effectively break down the collagen in these tough cuts of meat, you need to apply the additional energy (heat) over time, by cooking at a lower temperature over a longer period of time.

Why Barbecue?

Barbecue (slow smoking) is different than grilling because of the lower heat involved. At 140 degrees, the collagen begins to liquefy into gelatin. This is a slow process, it does not happen instantly when the meat temperature hits 140 deg F. It takes time – low and slow. So the longer you hold the meat temperature above 140 deg F, the more collagen will turn into gelatin.

- Same thing with the melting of the fat – it takes time.

- The protein muscle fibers start to relax and the juices are absorbed rather than squeezed out. Cooking barbecue in this low and slow fashion results in tender, succulent meats.

If you are experienced at cooking barbecue, you know about the “barbecue plateau” where your meat tends to get stuck at a certain temperature (around 165 deg F) and stay there. An experienced pit master knows this is when all the “good stuff” is happening… your collagen strands are unwinding, your fat is melting, and your muscle proteins are slowly relaxing instead of seizing up.

Tough cuts of meat like brisket and pork butts benefit from low temperature cooking as the collagen adds flavor to the meat. Less tough, more expensive cuts do not need this phase and can be cooked at high temperatures for shorter periods. That is why ribs take only a few hours and briskets take up to 20 hours.

The Magic Number

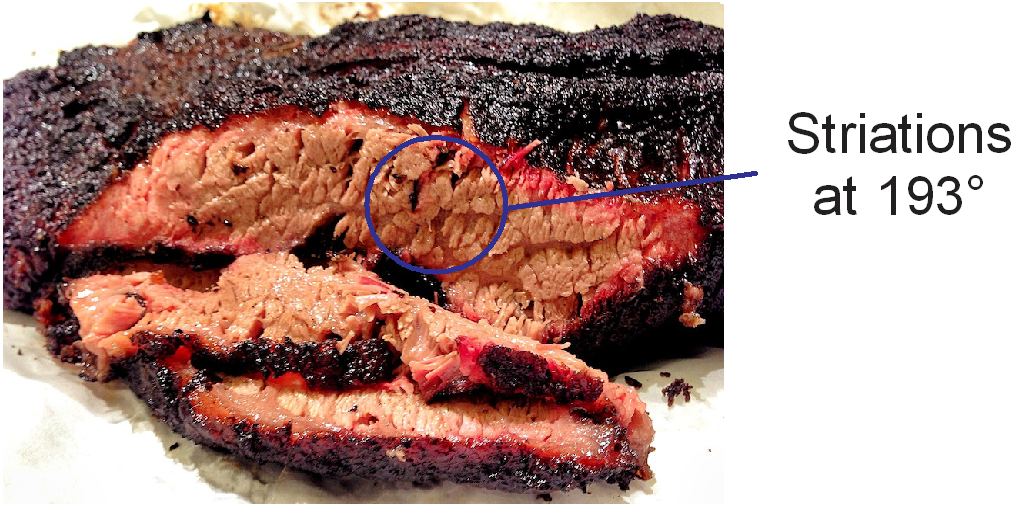

There is a magic number when barbecuing meat, specifically beef and pork. That number is 193. That is the temperature (Fahrenheit) where, if you have been cooking low-and-slow, you will find all of the collagen in your meat has dissolved and the meat takes on the texture of Real Barbecue. “Falling off the bone” is a phrase often used to describe this state of meaty grace.

While your meat will be

fully cooked at much lower temperatures, the key here is texture…and again,

referring to the collagen, this is the temperature where you can see that the

meat has physically changed from how it looked when it was just 3 or 4 degrees

cooler. Meat cooked to a lower temp

(say, 170 or 180) is often called “sliceable’.

A cross cut slice of ‘Sliceable’ meat will have a smoother texture with

less defined lines throughout.

Meat that is left to cook to that 193 is called ‘pullable’. This refers to the standard ‘pulled pork’ of

the Carolinas….barbecued pork which is then shredded with two forks into a pile

of luscious tender goodness. ‘Pullable’ meat will have more well defined

striations or little crevices, visible in a cross section of the meat.

So, the aim is to get your brisket or pork shoulder to that magic temperature, by cooking it low and slow…until it reaches that point of falling off the bone.

Conclusion

As there are many different traditions surrounding Barbecue, the one constant is that it is a perennial favorite around the world. Whether it’s Pulled Pork with Mustard Sauce from South Carolina, or Brisket served dry from deep in the heart of Texas, folks love their Barbecue.

Learning a little about the history and regional varieties is the first step to being able to make great barbecue at home. I hope this primer has been some help in that vein.

More Information

The BBQ FAQ:

http://www.eaglequest.com/~bbq/faq2/

NOTE:

This document was created from notes I’ve made over a number of years with information gleaned from multiple sources. At the time I began gathering info I did not document all of the source material so I apologize if I’ve used some information here without citation.

WIKIPEDIA entry for Barbecue:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Barbecue

A brief history of North Carolina pulled-pork barbecue:

http://www.ibiblio.org/lineback/bbq/origins.htm

A Brief History of Barbecue By Claire Suddath:

http://www.time.com/time/nation/article/0,8599,1908513,00.html#ixzz1DJJKq8eG